FRESHENING UP THE PAST

The Sainsbury Wing of London’s National Gallery is an example of postmodernism, a style that was already in decline when Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown won a controversial competition to build this addition. In the eyes of many, including this writer, the Sainsbury Wing, like James Stirling’s Neue Staatsgalerie in Stuttgart, is one of the (rare?) paragons of postmodernism. So it was with dismay that I read the headline in Dezeen: “Sainsbury Wing Revamp Approved.” Revamp? Although the Sainsbury Wing is a Grade I-listed building, it apparently needs freshening up. The freshening up includes removing some of the non-structural columns in the lobby as well as carving a large Trump-like sign into the Portland stone facade. The chief motivation for the alterations is the dubious decision to convert the Sainsbury Wing into the main entrance to the Gallery. The lobby rendering released by Selldorf Architects shows a rather banal space that reminds me of an airport lounge, with none of the quirky brilliance that characterized the Venturi Scott Brown design. The British architecture critic Hugh Pearman told Dezeen that the proposed alterations “would be damagingly destructive—sterilizing the original architectural character of the building.” What a shame.

FOREIGN SHORES

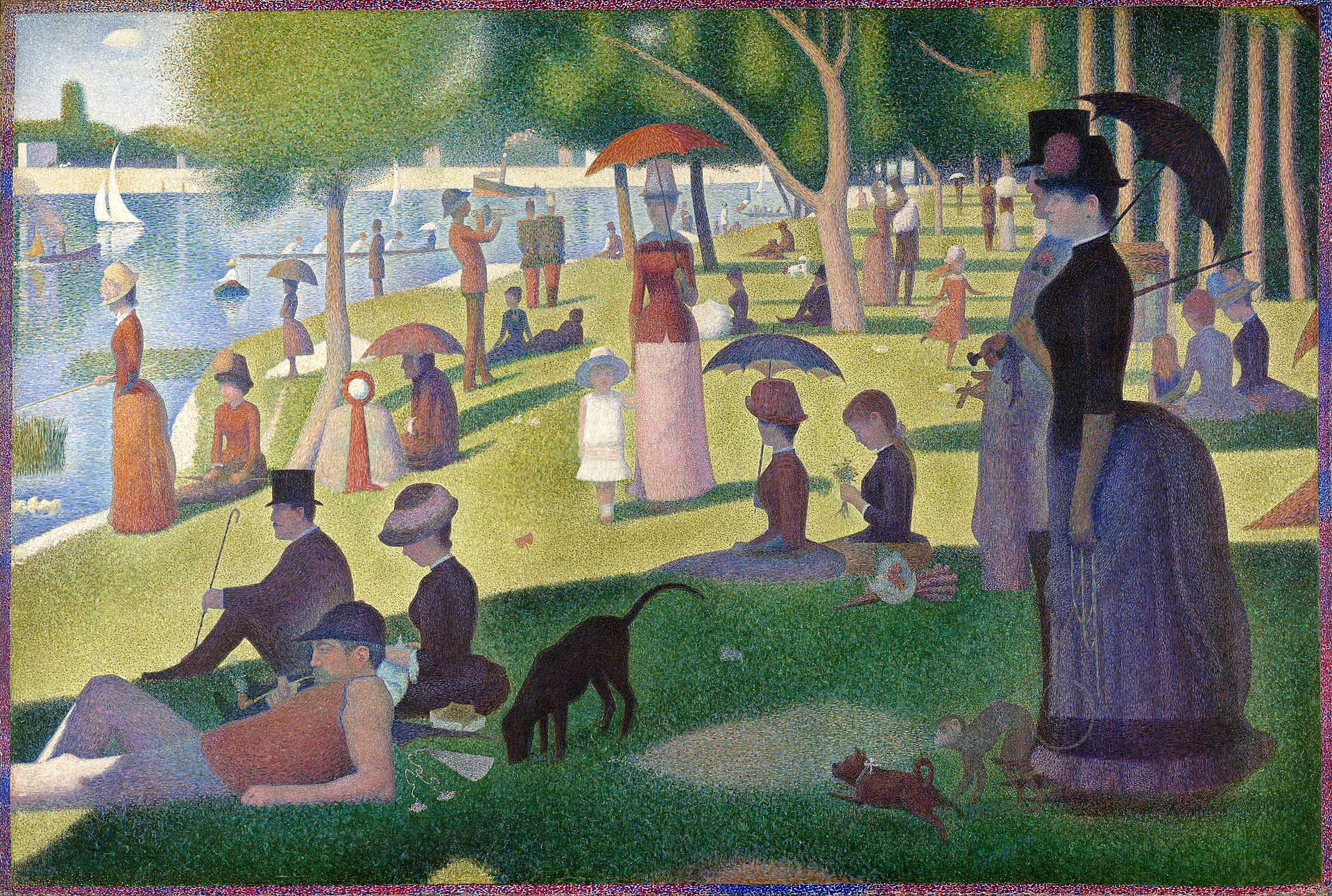

The Zhejiang University Press of Hangzhou has published Chinese translations of Home and Waiting for the Weekend. A reader of the latter will find a postcard with an image of Georges Seurat’s “A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grand Jatte,” which is referred to in the book and was on the jacket of the Viking edition, back in 1991. Nice. Zhejiang has also published a translation of One Good Turn, which is a natural history of the screwdriver and the screw. It’s printed on black paper–a first for me–and has a screw post binding. Like a shop manual!

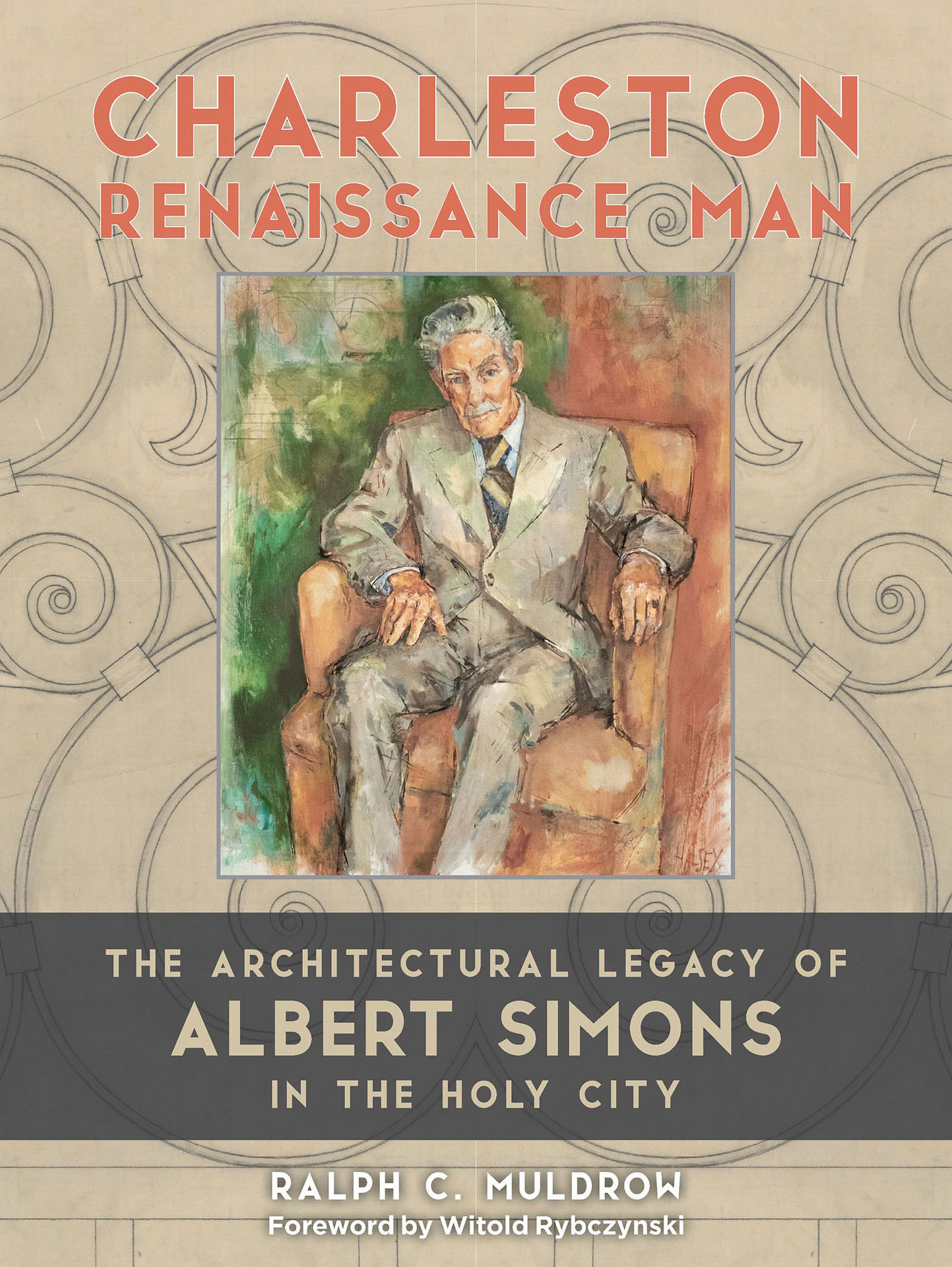

CHARLESTON RENAISSANCE MAN

My friend Ralph Muldrow has just published a book on the life and work of Albert Simons (1890-1980), an architect of Charleston, South Carolina. Simons (rhymes with persimmons) is an interesting figure. Trained as a classicist he practiced during the period when architectural modernism was emerging and gaining predominance. He was also a leading figure in the Charleston architectural preservation movement, which means he was a leading figure nationally, for in 1931, Charleston passed an ordinance creating a historic district—the first American city to do so. You can read my Foreword here.

JACK DIAMOND

The architect Jack Diamond (1932-2022) died last week. He was perhaps Canada’s leading architect. Yet no-one would refer to him as a starchitect. “It’s easy to do an iconic building,” he once said, “because it’s only solving one issue.” Diamond’s designs were never one-dimensional. His opera house in Toronto is a traditional horseshoe-shaped auditorium situated within an unprepossessing blue-black brick box whose chief feature is a glazed lobby facing one of the city’s main streets; dramatic, but hardly iconic—very Canadian. At $150 million in 2008, the cost of the Four Seasons Centre was modest as opera houses go, but more important was how the money was spent—on the hall and the interiors rather than on exterior architectural effects. Sadly Diamond would not be attending the gala reopening of his last project, the redone David Geffen Hall at Lincoln Center. The New York Times’ Michael Kimmelman, writing about the architecture of the hall, was rather mealy-mouthed in his back-handed compliment, “it is like the second-best-looking man in an old Hollywood film: generic, attractive enough, ceding center stage to the star, which is the music.” But ceding center stage to the music is the whole point, isn’t it?

SHEDS

Architecture mags these days cover a variety of topics—sustainable building materials, energy conservation, social equity; it seems that they have decided that building rather than architecture is their domain. But building and architecture are not the same. Nikolaus Pevsner’s introduction to his 1945 classic Outline of European Architecture began with this statement: “A bicycle shed is a building; Lincoln Cathedral is a piece of architecture.” In my beat-up paperback copy, purchased when I was a student, I underlined the sentence and pencilled a question mark in the margin. In those halcyon days I had a youthful reaction to Pevsner’s provocation; now I’m not so sure he was wrong. Pevsner said that what distinguished architecture was its goal of aesthetic appeal. After spending four years writing The Story of Architecture I would expand that claim. The ambition of architecture is not only beauty but also the desire to celebrate, honor, pay homage, and often to impress. That, and not size or cost or function, is what sets architecture apart from building. When Victor Louis was designing the Palais-Royale speculative mixed-use project in Paris in 1781, he gave it similar architectural qualities as his earlier Grand Théâtre de Bordeaux.

THIS IS THE PLACE

Architects and town planners often refer to a “sense of place” as a mark of authenticity. For example, Central Park has a sense of place, but a Walmart parking lot doesn’t. Nothing is as bad as placelessness—the term “placeless sprawl” appears in the first sentence of the Charter of the New Urbanism. It sounds like a logical extension to go from valuing a “sense of place” to “place-making.” But I’m not so sure. When Brigham Young arrived at Salt Lake Valley he is said to have exclaimed, “This is the place!” Young had the benefit of a previous celestial vision. I remember the first time I went to Chez Panisse, or saw the Empire State Building, or walked into the Guggenheim Museum; it was not only a question of design but of memory. We have all been to airport bars that work hard at creating a sense of place with period photos, team pennants, and other knickknacks. The harder they work at it, the more placeless they seem. On the other hand, the Cherry Street Tavern around the corner from where I live is for me a real place, not just because it has a nice wooden bar and old Bob Dylan posters,