MULTIPLE EXPRESSION

I heard a new architectural term today: “multiple expression.” It refers to changing the architectural style of the facade of a large building to make it appear to be two or more smaller buildings. This strikes me as profoundly un-architectural. It’s true that architects in the past have sometimes combined different styles to give the impression that a building grew by accretion over a long period—Addison Mizner did this in his shopping alley in Palm Beach. But this had to do with chronology, not size. Generally architects have welcomed the challenge of designing a looong facade, whether it was Bernini in St. Peter’s Square in the Vatican, or John Nash in a Regency terrace in London (above). Not that I have any objection to visual trickery—trompe-l’œuil can be delightful. But somehow “multiple expression” bespeaks a lack of confidence, a poverty of the imagination.

LOOKING BACK

For some reason the YouTube algorithm has been sending me videos of my old lectures: a recent lecture at Penn on ornament, a 2002 Toronto ideacity talk on Palladio, a 2013 talk at McGill University on architecture,and a talk about the history of the chair at the New York School of Interior Design. In 2011 I gave a lecture at the National Building Museum in Washington, DC. The occasion was the publishing of Makeshift Metropolis, a book about the ideas—good and bad—that have influenced the planning of our cities over the twentieth century. The four big ideas I talked about were: the City Beautiful movement; the garden city; Le Corbusier’s Ville Radieuse; and Jane Jacob’s idea of the humanist city. My main thesis was that American cities are driven by demand rather than supply, that is, by what people want rather than what city planners and architects suggest. I still think that’s true.

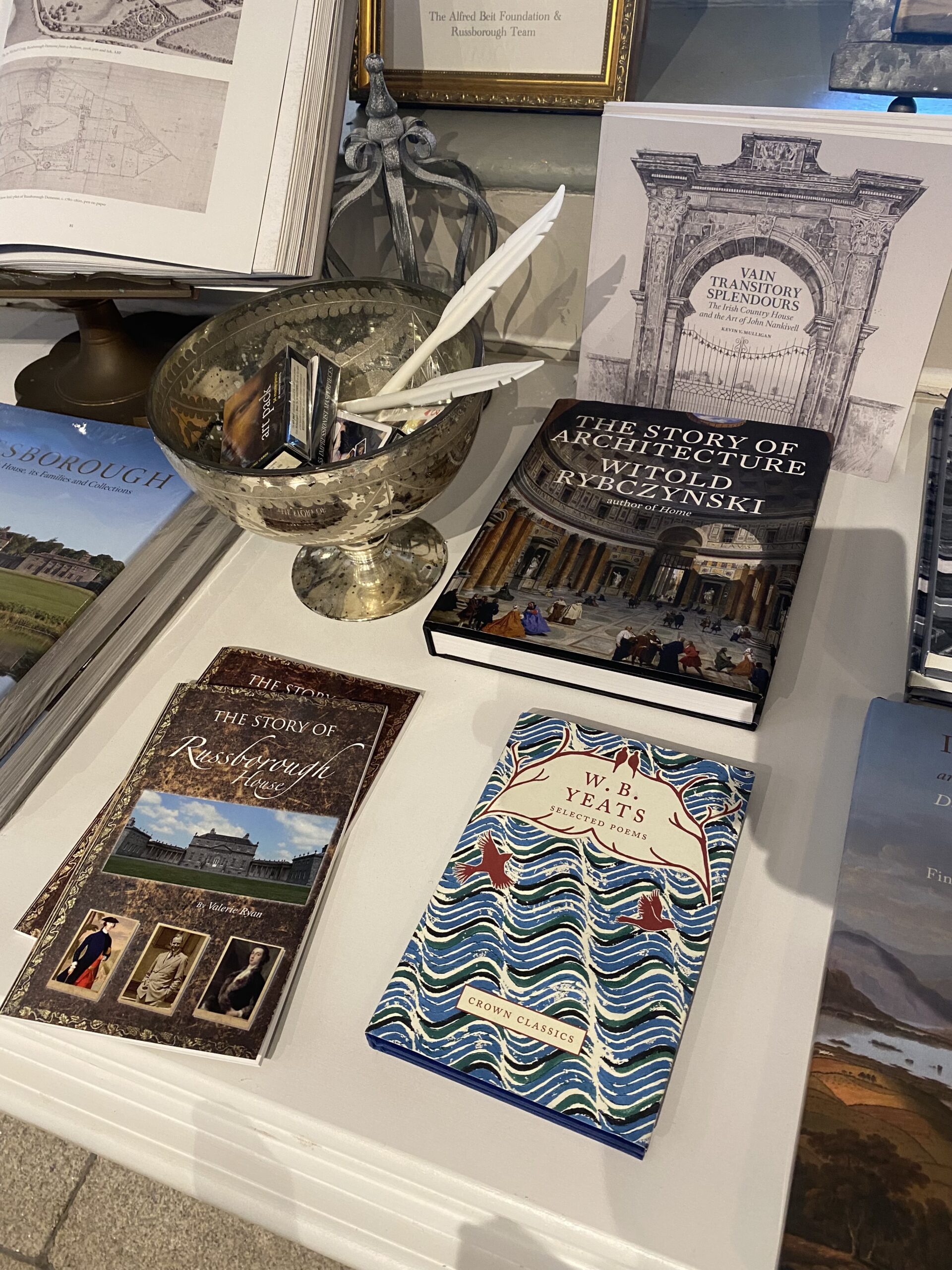

GOOD COMPANY

My friend Michael Imber sent me this. From Russborough House, a famous Palladian house in County Wicklow, Ireland, designed in 1741 by the German architect Richard Cassels, who introduced the style to Ireland. Cassels, known locally as Castle, also designed Leinster House, which was James Hoban’s model for the White House.

STREAMING

Wally Byam (1896-1962) built the first Airstream trailer in 1937 (it cost $795). He was trained as a lawyer but had a checkered career. In the 1930s there was a fad for travel trailers, and he tried that. The Airsteam was monocoque construction, streamlined and very light. Although the exterior looked like a Dymaxion car or an airship, there was no bare aluminum inside—wood paneling, over-stuffed seats, pretty curtains. Lots of plaid. Starting in 1951, Byam led “caravans,” groups of up to 200 Airstream owners, touring the US, Canada, Mexico, and Europe. The last caravan was from Capetown to Cairo! At night the Airstreams formed large circles, like Conestoga wagons.

I wrote about Byam and the Airstream in Taming the Tiger: The Struggle to Control Technology (1983). He was an unusual sort of architectural modernist. “Byam understood something his European contemporaries did not; while technology could be used to fashion a new way of life, it could also be used to redefine an old one.”

THE OLD URBANISM

Traditional urbanism is an easy sell; most people favor treed squares, fountains, and benches. People in Philadelphia crowd Rittenhouse Square, which was laid out in the 17th century, and whose Parisian details were planned by Paul Cret in 1913. The buildings lining the square are of many historical vintages: modern, moderne, and neoclassical. In a hundred years, in 2123, I suspect there will be even more variety, reflecting changed architectural tastes, changed materials, and changed styles. But the square itself, and the streets that define it, will likely be familiar; it’s not so easy to alter rights of way. This underscores an important distinction. Urbanism and architecture observe different time lines. It may be a mistake to tie traditional urbanism to traditional architecture, as many proponents do. The two are entirely different animals.

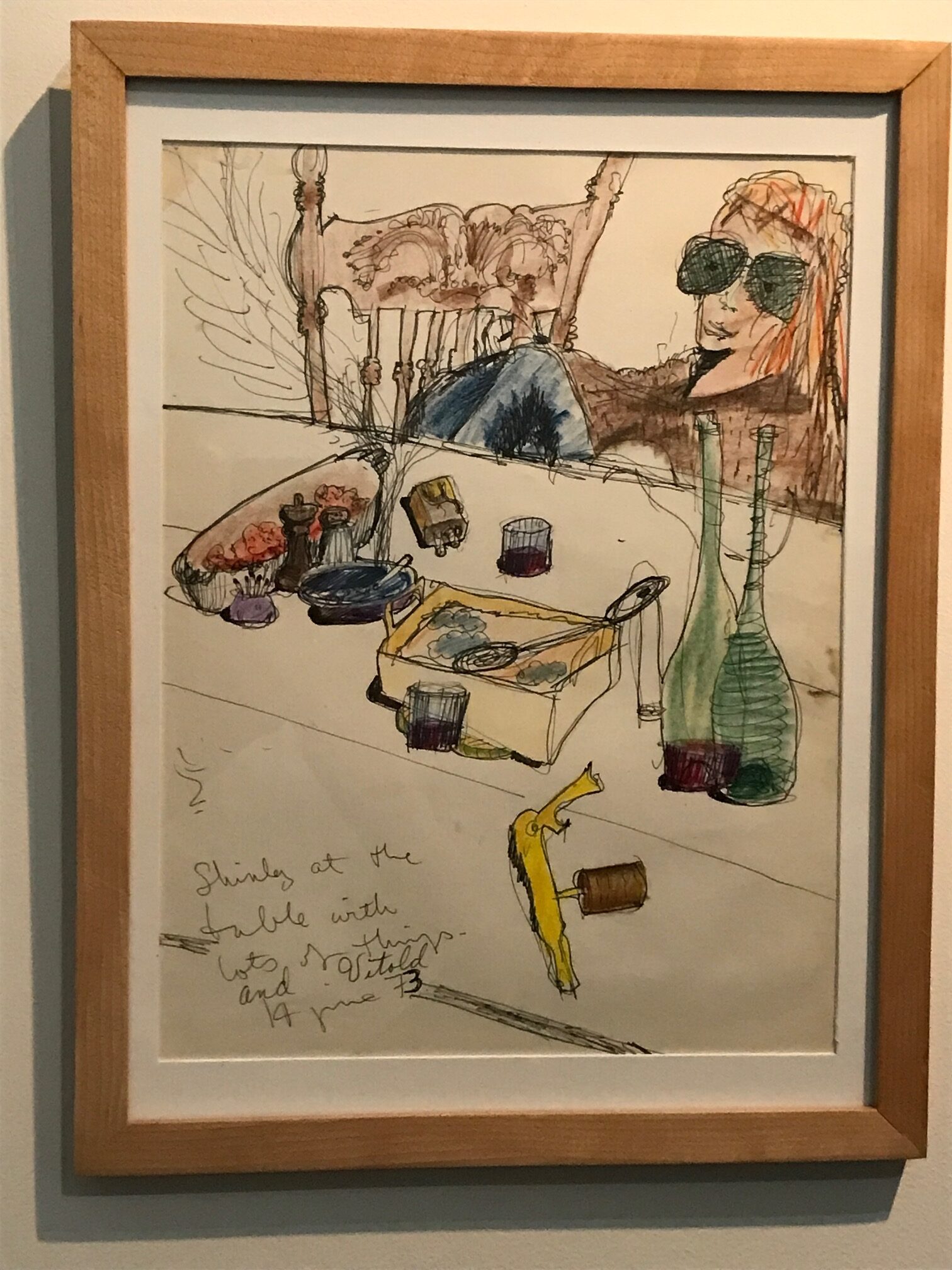

REMEMBERING

I have different ways of remembering. I have framed an old sketch I came across that shows her in the first home we shared. “Shirley at the table with lots of things” I had written. “And Vitold” she’d added. I buy flowers; for the house, I say to myself, but really for her. I keep her favorite necklet on her night-table, sometimes I rotate it with bracelets and other pieces. Once in a rare while I spray her Sisley Eau de Soir—there is just a little left. What will I do when it runs out? We talk: Good morning I say. I tell her my plans for the day. I’m going shopping, I think I’ll stop at the wine store. I toast her when I open the bottle. I almost say “Santé,” but I stop myself. Not that.