WITHOUT SHIRLEY

It is the third year of my life without Shirley. The period of intense grief has passed, but with it also the immediacy of her absence. I still talk to her, and I still occasionally get the feeling that she will knock on my door, like a character in a Hollywood paranormal movie. I would tell her about what she’s missed: the time the Schuylkill breached its banks and our building got flooded; my visit two summers ago to Northeast Harbor in Maine, where we once spent a happy week; my last book, my next book. In truth, there is not much to relate. My life has slowed down, it is as if someone had lowered my setting to half speed.

UNSTICKING

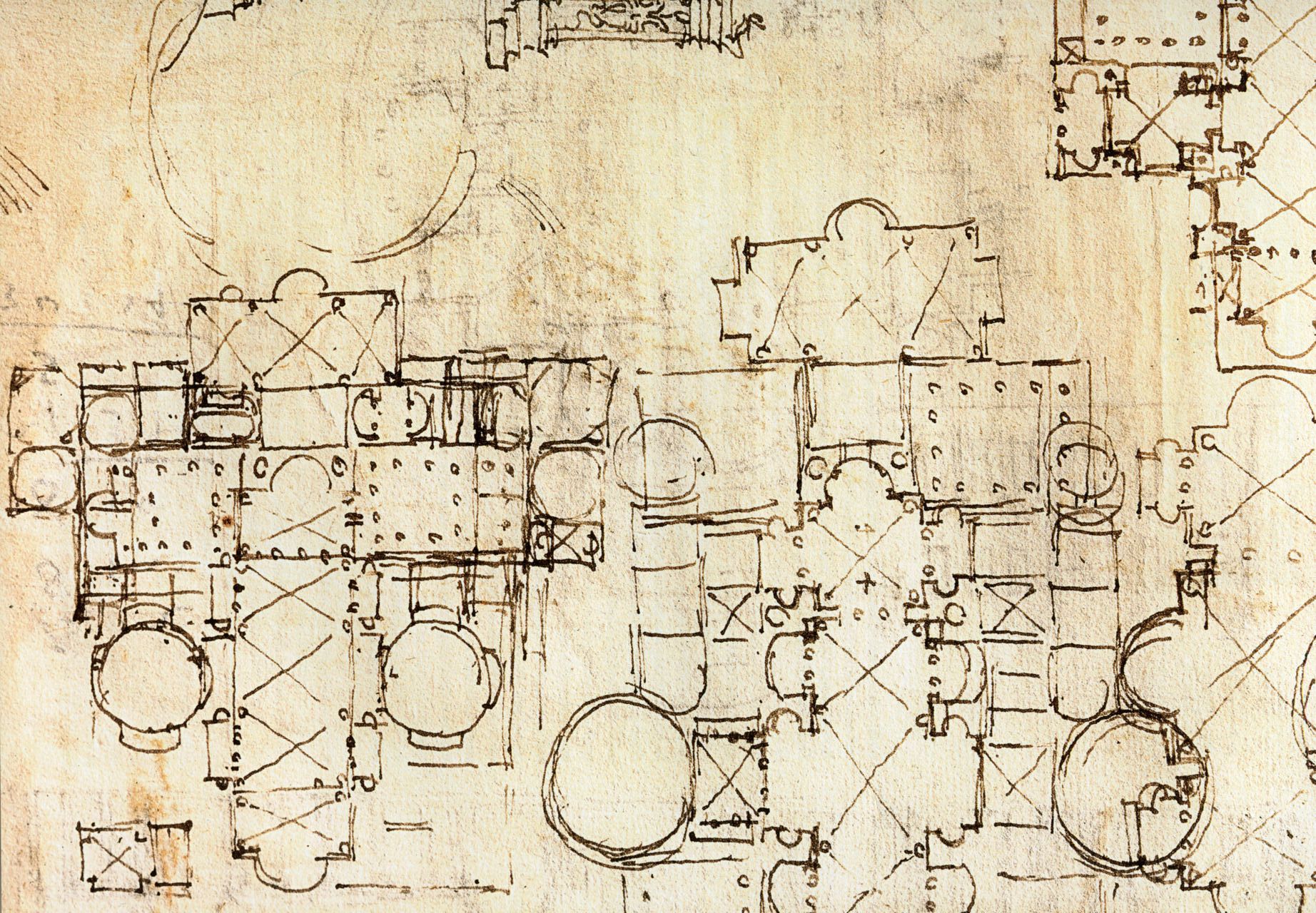

“What is to be done?” my friend asked. We had been discussing the rather low current state of architecture, countless glass boxes, undisciplined and arbitrary designs, a profession at sea. We have been here before. Because fashion is an unavoidable aspect of architecture—not the main thing, but always lurking in the background—architecture does not evolve steadily like science or technology, it swings back and forth and occasionally gets grounded. That happened in the United States in the late nineteenth century, and it took a Richardson and a McKim to shake it out of its lethargy. Something similar happened in the 1970s, after the International Style had worn itself out. James Stirling put it well when he said at the time “The language itself was so reductive that only exceptional people could design modern buildings in a way that was interesting. It got stuck and it will have to unstick itself to move one.” Stirling, along with Graves and Venturi, looked to the past to help with that unsticking, but the result—Postmodernism—proved thin gruel. Can digital computing provide a more substantive answer? Proponents trumpet the virtues of “parametric architecture,” but design technology (the pencil?) and constructional breakthroughs (reinforced concrete?) have rarely moved the architectural needle.

IRONY

Describing the Königliches Schloss, the rebuilt imperial palace in Berlin, Michael J. Lewis wrote recently in The New Criterion: “It is not so much a recreation of the palace as a workmanlike scale model of the original, placed on the original site, and with something of the gift that Robert Venturi gave to historic preservation, which is a saving leaven of self-aware irony.” This is a useful insight: irony is a way for modernists to deal with the past without actually acknowledging its primacy. But was Venturi’s “leaven of self-aware irony” a gift or a poison pill? Venturi’s firm lost important commissions such as the Philadelphia concert hall precisely because clients did not appreciate ironic, or sometimes downright jokey, architectural asides. Most clients—Vanna Venturi aside—are loathe to see their money spent on something as insubstantial and potentially risible as irony. And irony gets stale over time; is that why so many VSB buildings have fared poorly, being insensitively enlarged, or demolished as in the recent case of the Abrams House (see above) in Pittsburgh? Absent idiosyncratic follies and amusement parks, architecture is more serious than that.

WITHOUT THINKING

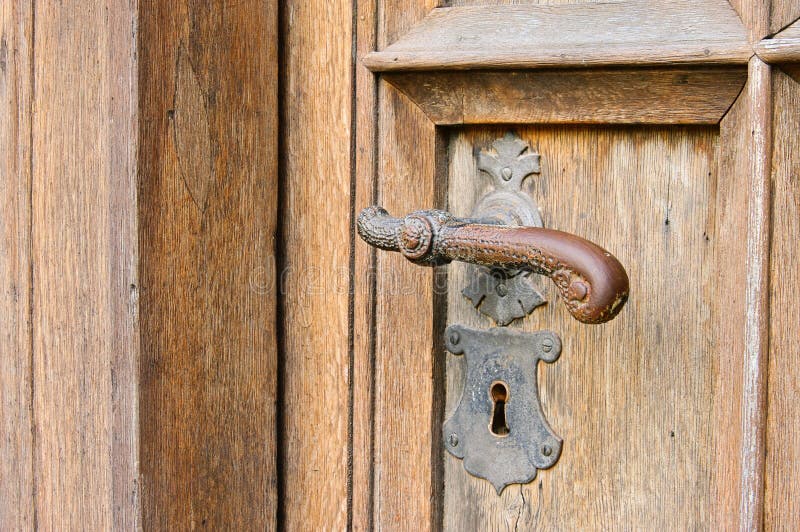

[et_pb_section fb_built=”1″ _builder_version=”3.22″][et_pb_row _builder_version=”3.25″ background_size=”initial” background_position=”top_left” background_repeat=”repeat”][et_pb_column type=”4_4″ _builder_version=”3.25″ custom_padding=”|||” custom_padding__hover=”|||”][et_pb_text _builder_version=”3.27.4″ background_size=”initial” background_position=”top_left” background_repeat=”repeat”]The philosopher Alfred North Whitehead wrote that “Civilization advances by extending the number of important operations which we can perform without thinking about them.” It seems to me that this profound observation can be applied to buildings. I open a door, the door handle is at a certain height, near the edge of the door that swings open into the room I am entering. If it is a lever handle, I turn it down—not up—to open the door. Where is the light switch? On the inside wall, on the side where the door opens. I perform all these operations without thinking about them. And when I’ve designed houses, I’ve used such details without thinking. I recently visited a Louis Kahn-designed house where the architect had consciously re-thought basic domestic solutions. All the inside doors were sliding pocket doors instead of swing doors, and the windows were fixed glass with little panels that opened for ventilation, instead of conventional double-hung windows. It seemed to me like a civilizational step backward.

[/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row][/et_pb_section]

THEORY

I recently came across two interviews on YouTube on “Theory of Architecture,” one by Mark Wigley, the other by Patrik Schumacher. Wigley sounded like a middle-aged architecture student. Schumacher was rather pedantic in his Germanic way, and he made some outrageous claims: Romanesque and Gothic buildings were not really architecture because they didn’t have architects, drawings, or texts. The last seemed important to him: you needed the “discourse” to make real architecture.

Schumacher did say one interesting thing. That the architect needed to understand his time in order to function properly. He did not elaborate, but the point is well taken—Mies said much the same thing: “Architecture is the will of an epoch translated into space.” It’s not what the architect wants, it’s what the times demand.

But I wonder if Wigley, Schumacher and their ilk do really understand their time. Or is it Bob Stern, with his eclecticism and post-modern approach?

What a sorry state our field has descended to when that is the choice!

VENERATION

I recently spoke in Charleston at the first national meeting of the Institute of Classical Architecture & Art. The ICAA is, in its own words, “committed to promoting and preserving the practice, understanding, and appreciation of classical design.” Exactly what is “classical design”? According to Wiki, “classical architecture usually denotes architecture which is more or less consciously derived from the principles of Greek and Roman architecture of classical antiquity.” That is the art historical definition, but judging from the Professional Portfolio regularly published in the ICAA’s journal, The Classicist, Gothic, Moderne, Art Deco, and various vernacular residential styles such as Shingle Style, Mediterranean, and Craftsman, also qualify. If this sounds reactionary—“anything but Modern”—well, maybe it is. But therein lies a challenge. Architects have always looked back in order to move forward, as James Stirling wisely observed, but move forward they do. This was true of Stirling, but equally true of his predecessors such as Bertram Goodhue, Paul Cret, and Raymond Hood, the last generation before Modernism’s ascendancy in the postwar era. These architects saw the past, including the Classical past, not as a strait jacket but as a springboard. The iconoclastic Goodhue once remarked, “All rules in architecture save absolutely basic ones are outside the subject.