Ask the People

by Witold | Oct 9, 2012 | Architecture, Modern life, Urbanism

Speaking recently at a British conference on urbanism, Daniel Libeskind called for a greater degree of public participation in the design process. “The people have to be empowered to be involved in shaping the program, not just the program but also the actual space,” he said. Let the voice of the people be heard! I was reminded of this tired nostrum as I was watching Seven Days in May. In a taped commentary, director John Frankenheimer several times emphasized that this excellent movie, shot in 1963, could not be made today (he died in 2004). Imagine, a political thriller without a shooting, a fight, or even a car chase! One of the differences in 1963 was the absence of preview screenings. Frankenheimer speculated that had the film been subjected to a test viewing, as almost all movies are today, someone would have complained about the long scenes and extended dialogue, or the complicate plot and the lack of action, and changes would have been ordered.

Fredric March (holding telephone), Edmond O'Brien and Martin Balsam in "Seven Days in May."

The architectural equivalents of the pre-release preview are the community boards, design review panels, and neighborhood oversight committees that “screen” new projects before they are built. It is virtually impossible to realize an urban building today without considerable input from the public. Sounds democratic, but the problem is that the The Public is often those who shout loudest and complain the most, well-meaning pressure groups, single-issue lobbies, and disgruntled individuals. It is hard to believe that more of this process, which tends to produce improvised compromises and mealy-mouthed consensus, would really raise the quality of the built environment.

The New-New Thing

by Witold | Oct 3, 2012 | Architects, Architecture

The front page of today’s New York Times Arts section features two articles that sum up the state of architecture today. The newspaper’s music critic Anthony Tommasini reviews an inaugural performance in new concert hall in Sonoma State University, and Robin Pogrebin reports on Frank Gehry’s appointment to design an arts campus in Miami. The architect of the hall at Sonoma State is William Rawn, whose Seiji Ozawa Hall in Tanglewood has been acoustically rated as the fourth-best concert hall in the nation. Tommasini calls Weill Hall “a beautiful space” and the sound of the hall “rich, clear and true” (although the Times architecture critic chose not to weigh in on the design of the hall). In other words, the critique of Weill Hall is based on the building’s actual performance as a music venue. By contrast, the Miami story is about a building that has not yet been built, not even designed. Gehry is a remarkable architect, but does his mere selection by a client really qualify as news? The answer is yes, for in architecture today, the new-new thing rules. It’s true that architects have always been more interested in design than in reality, that’s why prizes are regularly awarded to buildings before they are built, which is rather like rating a restaurant on the basis of its menu, without tasting the dishes. Similarly, unbuilt projects are critiqued in the media on the basis of a model or a sketch, while completed buildings are assessed after a “press day,” before they are actually put into use. But the time to evaluate a building is after years of use, when the rough edges have been worn smooth, and it is possible to judge the durability—aesthetically as well as physically—of the design. But, of course, that would not be news.

Foxes and Hedgehogs

by Witold | Sep 30, 2012 | Architects, Architecture

The philosopher Isaiah Berlin wrote a famous essay based on a saying attributed to the ancient Greek poet, Archilochus: “The fox knows many things, but the hedgehog knows one big thing.” Berlin was referring to writers and thinkers—he characterized Plato, Nietzsche, and Proust as hedgehogs, Shakespeare, Goethe, and Pushkin as foxes. I was visiting Seattle this week, and two buildings almost side by side, the Seattle Public Library (2004) and the City Hall (2005), reminded me that the metaphor holds true for architects as well. Rem Koolhaas and Joshua Prince-Ramus, the architects of the library, are definitely hedgehogs; they have one big idea that they flog for all it’s worth. Glass, glass, glass. No details, no facades, no relation to the surroundings—the crystalline shape is awkwardly parachuted into steeply sloping site. Peter Bohlin, on the other hand, is a (sly) fox. Instead of a Big Idea, the city hall addresses its function, its site, its views, its materials, and its construction in many small—and not so small—ways. We have become so used to signature buildings that it is almost a surprise to encounter a public building that is not trying to be an icon. Unlike the library, the city hall is neither puzzling nor confusing. Here are the offices, here’s the council chamber, here’s the entrance, here’s a place to sit and have lunch, and here’s how the whole thing is put together. The library is a prickly presence in the city; the city hall flits lightly through its urban surroundings.

Ask the Pigs

by Witold | Sep 22, 2012 | Architecture

“If we want to understand the physical environment we should not ask architects about it,” writes Jonathan Meade in his new book, Museum Without Walls, (excerpted here). “After all, if we want to understand charcuterie we don’t seek the opinion of pigs.” Meades’s point is that the environment is much too valuable—and much too complex—to be entrusted to a single profession. Designing buildings is a perfectly respectable occupation, but architects want more, they want to create places. But places are created by their occupants over time, not by designers on paper, and most architectural attempts at place-making, such as megastructures, public housing projects, and planned communities, have run aground. I’m not sure when architects’ ambition expanded to encompass “the environment,” as opposed to buildings. Team Ten, which promoted an environmental view of building, met in Otterlo in 1959, which was the same year that the school of architecture at Berkeley was renamed the College of Environmental Design. Christopher Alexander’s Notes on the Synthesis of Form appeared in 1964. Moshe Safdie built Habitat in 1967. Habitat is a fine project, but only because the city of Montreal is next door—a city of Habitats would be insupportable. Decades later, when Safdie master planned the new city of Modi’in inIsrael, he did not design the whole thing but made sure that many architects, developers, and builders were involved. The result is less perfect but more real.

By the Numbers

by Witold | Sep 18, 2012 | Architecture

I recently heard a talk by David Gottfried, the founder of the U.S. Green Building Council, which pioneered the LEED system for rating the greenness of buildings. Gottfried is no longer associated with USGBC and was promoting his latest project, a book titled Greening My Life which, as near as I could figure, was a rating system to score your personal happiness. There is something about numerical rating systems that appeals to Americans. We have GREs, SATs, LSATs, GMATs, Best College Rankings, teacher evaluations, Best Place to Live, opinion surveys, and political polls. This abiding belief in the power of numbers may have to do with living in a large heterogeneous country whose population no longer shares a common set of values. Or, perhaps it is an outgrowth of democracy itself, which is, after all, based on counting heads. No doubt, a fascination with numerical rating accounts for the widespread adoption of LEED. There are Silver, Gold and Platinum buildings, just like credit cards. Most people assume that a Platinum building performs better than a Silver building. Maybe it does, but LEED doesn’t actually score performance, as some other rating systems do, it scores design. You get so many points for having a bike rack, whether or not there are any bicycles in it. The puzzle is that so many LEED buildings are entirely glass, which seems counterintuitive. But that’s design by the numbers.

The Master Builders

by Witold | Sep 16, 2012 | Architects, Architecture, Modern life

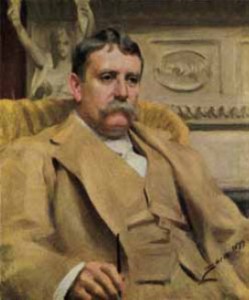

I attended a meeting of the Design Futures Council ambitiously billed as a “Leadership Summit on Sustainability.” Present were engineers and representatives of the building materials industry (whose parent organizations were the chief sponsors of the event), but most of the participants were architects. The last group voiced a recurring theme. “It is important to think not only about buildings but about neighborhoods, and not only neighborhoods but cities, or preferably regions. Better still, the entire planet.” During the meeting, one architect voiced the opinion that architects could design anything. Oh, really? Architects are trained to design buildings. A few architects, like Eames and Saarinen, have designed great furniture, although that is the exception rather than the rule. And most architects are ill-equipped to function as city and regional planners, just look at the urban renewal fiascos of the 1960s. Designing buildings is a perfectly honorable profession, and if the buildings are functional and beautiful, the profession will be respected and listened to, as it was in the early 1900s. Sadly, that is not the case today. Although a few architects are almost household names, they are in the celebrity category, and their fame is as brittle and fleeting as that of Hollywood stars. As for the largest firms, which employ upward of a thousand people and have offices around the world, they are bigger but not better. None exerts the artistic and political clout of a Daniel Burnham or a Charles McKim. “Leadership” remains an elusive chimera.

Daniel H. Burnham painted by Anders Zorn

Portlandia

by Witold | Sep 11, 2012 | Modern life, Urbanism

Dateline: Portland, Oregon. This city is an odd mixture of urbanity and provincialism. A walkable downtown with light rail but with more backpacks than attaché cases—that’s not so odd, but people carrying sleeping bags on the street is. Everybody waits for the traffic lights to change—that appeals to the orderly Canadian part of my soul. Cities are about obeying rules in order to live together. Portland isn’t exactly Manhattan, but I like it. Perhaps this is the new “urban-light living” that a recent article in the Atlantic talked about.

The late nineteenth and early twentieth century buildings are derivative—this could be Buffalo or Rochester—and equally sophisticated. The current crop of office buildings is no less derivative but done with considerably less conviction. A little of this, a little of that. Graves’s Portlandia Building is getting a bit frayed (although Ray Kaskey’s statue looks as good as the first time I saw it, years ago), and so is the Equitable Building, designed by Graves’s nemesis, Pietro Belluschi (the first real modernist office building in the US). But compared to the current generation of hacks, Belluschi and Graves were at least trying to make a coherent statement. I look for Filson’s, but it’s moved to a new location; L.L. Bean has just moved away, period. John Helmer Haberdasher is still there. I must have bought my first hat from this shop 30 years ago. I buy an Italian linen cap, for old times sake.

State Caps

by Witold | Sep 10, 2012 | Architects, Architecture

American state capitol buildings are traditionally a smaller version of the U.S. Capitol, complete with central dome; you can find them in Montpelier, Harrisburg, Little Rock, and Salt Lake City. The state capitol in Lincoln, Nebraska is different. There is a small gold dome, but it’s on top of a fifteen-storey office tower. The architect was Bertrand Grosvenor Goodhue. He won a 1920 national competition against formidable competition; second and third places were was taken by John Russell Pope and McKim, Mead & White, who both designed classical schemes with the familiar domes. The fourth-place finisher was Paul Cret who dispensed with the dome and proposed a low, building in a simplified classical style, the centerpiece crowned by sculpted buffaloes. Goodhue’s design was even more radical: a free interpretation of classicism that dispensed with columns and entablatures and blended classicism with a Gothic sensibility (Goodhue had designed many Gothic Revival buildings with his then-partner Ralph Adams Cram). The Nebraska building is not a stylistic pastiche, however, more like a modern riff on old themes. The modernity is underscored by the artistic elements in the building, many on prairie themes (including “The Sower” that stands atop the dome), the work of sculptor Lee Lawrie. This was a moment in American architecture when art and architecture happily complemented each other (see Rockefeller Center, where Lawrie also worked, for another example). It was also a moment when architects such as Goodhue and Cret were pushing the boundaries of traditional styles to discover a modern, American version. This remains another one of those “roads not taken,” as European modernism swept the scene, and such stylistic exploration—and artist-architect collaborations—became a thing of the past.

Getyourshittogether

by Witold | Sep 3, 2012 | Architecture

And now for something completely different.

The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation has turned its sights on a new global problem: sanitation. The foundation has committed $3 million to support research that has as its goal to “reinvent the toilet as a stand-alone unit without piped-in water, a sewer connection, or outside electricity—all for less than 5 cents a day.” “Reinvent the toilet” outré, but it isn’t. Children playing around a sparkling water pump are more photogenic than a well-functioning toilet, but inadequately treated human waste is the source of most water-transmitted diseases. And since running water supply is in short supply in third world countries, never mind adequate sewage treatment, the conventional flush toilet is not an option—a waterless toilet makes sense.

I don’t know what the Gates project will come up with, but I would be surprised if composting wasn’t a part of the solution. A typical adult excretes about half a pound of feces daily and between one and two quarts of urine, and since composting requires dry conditions, getting rid of the liquid is a problem. Most composting toilets use some combination of heat and induced ventilation.

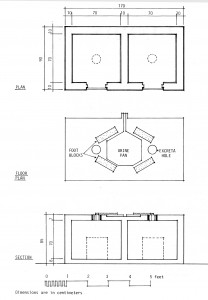

An ingenious composting toilet, the Gopuri, designed by Appasheb Patwardan in India in the 1940s, takes advantage of a special characteristic of human excreta: feces transmit pathogens, but urine is sterile. The Gopuri separates solid and liquid waste, which occurs naturally in a squatting position. A handful of ashes is sprinkled over the waste after each use. The toilet consists of two vaults. When one is full, it is sealed up, and the adjoining vault is emptied and put into use. The contents decompose anaerobically; the holding period is typically 3-6 months. The urine is disposed of immediately; the compost is used in agriculture. Thousands of Gopuri toilets were installed in the state of Maharashtra. A version of the Gopuri is reported to have been used with success in North Vietnam in the 1960s. There have been demonstration projects in a number of countries.

Stop the Five Gallon Flush, the classic 1973 guide from McGill University’s Minimum Cost Housing Group, featured in the Whole Earth Catalog, describes 80 alternative sanitation systems, including the Gopuri, and is available free online.

Style Wars

by Witold | Aug 28, 2012 | Architecture

Some classicists have called for a “war” with architectural modernists. While this sounds rousing, I believe it widely misses the mark.

For one thing, it creates a straw man called The Modernist. As if you could really lump Thom Mayne, Renzo Piano, Peter Bohlin and Moshe Safdie together. Modernism is as internally riven as the Republican party. The Koolhaas-Hadid-Libeskind fringe receives media attention, but many of the big serious jobs go to the Piano-Foster-Rogers faction. The Centre Pompidou was seen as the swan song of so-called high-tech design, in fact it was the beginning of a style that has come to dominate a variety of building types: airports, museums, office towers. There is also a reaction within modernism to the excesses of Koolhaas and company in the form of much more “traditional” and dare I say intelligent wing that includes Peter Bohlin, Bill Rawn, and Jack Diamond. They often pick up the pieces after their glamorous colleagues. For example, Diamond is completing a ballet-opera house, the Mariinsky II, after two failed competition entries, the first by Eric Owen Moss, the second by Dominique Perrault failed to produce a satisfactory result.

I do not include Frank Gehry. He is sui generis, more a Gaudi figure than a Le Corbusier let alone a Mies. He should be valued, but not imitated. Incidentally, I have seen the model of the proposed Facebook headquarters, and it’s hardly Gehryesque, nor iconic (and actually much more appealing than Foster’s donut for Apple).

Some years ago, I think in 2002, I participated in an Institute for Classical Architecture symposium. I remember Robert A. M. Stern chastising the audience. It’s not enough to design expensive houses, he said, if classicism is to survive it has to expand into public buildings. Well, in the intervening decade, Stern, David Schwarz, Allan Greenberg, and Tom Beeby have done exactly that. There have been traditional public libraries, concert halls, and courthouses, as well as campus buildings, apartment buildings, and soon, a presidential library. I say “traditional” rather than classical for all these designers are eclectics. That is a strong card to play with clients, as John Russell Pope, Charles A. Platt, Paul Cret, Bertram Goodhue, and Ralph Adams Cram all understood.

It is clients, not competing architects, who are the key to a style’s survival. It is true that at the margins, politicking and intrigue play a role, but ultimately, it is clients not architects who decide what to build. Or not to build. That is why Frank Furness’s career foundered, as did Paul Rudolph’s, and why Louis Kahn’s rather ascetic architecture found few takers. If people like it, they will ask for it (that’s why Venetian Gothic lasted well into the Renaissance—the Venetians simply liked it). As for that old bugaboo—“educating the public”—it didn’t work for the modernists and it is unlikely to work for the classicists.

The modern American public has grown to expect a range of choices in food, dress, entertainment, culture, and so on. So why should architecture be exempt? I don’t see a world where classicism replaces modernism, even less where modernism conveniently disappears. “You cannot not know history” said Philip Johnson. He was reminding modernists that the past matters. But the immediate modernist past matters too. There are still lessons to be learned from Aalto, Mies, and Kahn, and an architect—any architect—would be foolish to ignore them. What I do see is an uneasy (at least for architects) coexistence. This is not a call for complacency, but neither is it a reason for pie-in-the-sky appeals to battle.

Sorry to be long-winded. I am finishing a book on this subject so it’s uppermost in my mind.

THE LATEST

Coming October 8