Kahn’t Do It

by Witold | Dec 9, 2012 | Architecture, Urbanism

A photograph by New York Times photographer Bruce Buck accompanies an article on the wonderful renovation of the Yale University Art Gallery. The gallery was built in three stages: a tall 1866 Ruskinian Gothic first phase by Peter Bonnett Wight (right); a 1928 Florentine Gothic horizontal portion by Egerton Swartwout; and a 1953 addition by Louis Kahn. What Buck’s photo clearly shows is the insensitivity of Kahn’s addition. It is not a question of style—Swartwout did not follow Wight’s lead either—but of massing. The Swartwout wing was rudely truncated by a brick party wall, and was obviously intended to be completed at some future date. Not only does Kahn not complete the work of his fellow architect, he insensitively pulls back to reveal the utilitarian party wall, leaving Swartwout with his metaphorical pants down. In addition, the cavity along Chapel Street does nothing to balance the composition, and only accentuates the difference between Kahn and Swartwout’s buildings—as it was presumably intended to do.

Speaking Ill

by Witold | Dec 7, 2012 | Architects, Modern life, Urbanism

One should not speak ill of the dead, it is said. Yet in a week fill with encomiums for Dave Brubeck (1920-2012) and Oscar Niemeyer (1907-2012) it is hard to hold back. When I started listening to jazz, in the late 1950s, the Dave Brubeck Quartet was already famous—or at least as famous as jazz musicians got at that time. I loved Paul Desmond, and Joe Morello could do no wrong (I was a drummer), but I never warmed to Brubeck himself. Me and my friends much preferred Ahmad Jamal, Monk, and Bill Evans.

Nor was I ever an admirer of Oscar Niemeyer. His curvy, rather simplistic one-note architecture never appealed to me. Nor did his authoritarian ideas about city planning. Robert Hughes called the city of Brasilia“a Carioca parody of La Ville Radieuse.” And so it is, a dystopian parody, “an expensive and ugly testimony to the fact that, when men think in terms of abstract space rather than real place, of single rather than multiple meanings, and of political aspirations instead of human needs, they tend to produce miles of jerry-built nowhere.”

Simply Ike

by Witold | Nov 30, 2012 | Architecture, Modern life

The final review of Frank Gehry’s design for the Eisenhower Memorial in Washington, D.C., has been postponed yet again and the project seems more and more likely to be shelved. In a recent letter to Sen. Daniel Inouye, John S. D. Eisenhower, the President’s son, raises an issue that has nothing to do with the quality of Gehry’s design (which I have supported), nor with the over-wrought classical-modernist debate. Why couldn’t the memorial simply be “a green open space with a statue in the middle” he asks? Good question. Ever since the FDR Memorial spread over more than seven acres, memorial sponsors have felt the need to appropriate large sites, and then fill them up with water basins, fountains, figures, walls, and reams of quotations. The lackluster Korean War Memorial occupies over two acres, the Vietnam Veterans Memorial uses three acres, Martin Luther King Jr.’s overblown memorial sits on four acres, and the memorial to World War II consumes no less than seven. John Eisenhower’s suggestion of turning the four acres of the proposed Eisenhower memorial into a green square with a single statue of the President would reverse this trend. The challenge would be to find a modern sculptor who is up to the task of creating not merely a depiction of the president-general, but a work that captures his somewhat elusive mixture of modesty, shrewdness, and grit. The moving statue of Eleanor Roosevelt by Penelope Jencks in Riverside Park is one model. The memorial to Winston Churchill in Parliament Square in Westminster is another. Ivor Roberts-Jones’s bronze is twelve-feet tall and stands on a plain granite block inscribed with one word—CHURCHILL. The Eisenhower memorial could say simply IKE.

Image and Reality

by Witold | Nov 29, 2012 | Architects, Architecture

Michelangelo Sabatino, who is researching the Canadian architect Arthur Erickson (1924-2009), recently sent me photographs that he had taken while visiting an early work by the architect. The 1959 Filberg house is in Comox, on Vancouver Island in British Columbia, and is particularly important since it launched Erickson on a stellar career that made him into Canada’s first internationally famous architect.

Sabatino’s photo (left) shows a rather, well, glitzy interior. Compare this view with what a professional architectural photographer does with the same interior (right). The angle is more interesting, the reflections are deeper, the forms balance each other; the room is still opulent, but no longer glitzy. In a forthcoming book, How Architecture Works, I compare architectural photography to portrait photography, whose purpose is to flatter the subject, to set it off to the greatest advantage, and to eliminate anything that detracts from this purpose. How often have we visited a building that we have previously seen exclusively in photographs, only to be disappointed, or at least surprised. Incidentally, the Filberg house may be an an example of Fifties taste, but that does not seem to have hurt its appeal, since it is listed for sale for six million dollars.

Game-Changer?

by Witold | Nov 26, 2012 | Housing

There is some evidence that after five years the housing industry is showing signs of recovery. The sixty-four-thousand-dollar question is what form the recovery will take. It all depends on who you listen to. Those who believe that economic recovery will be spear-headed by consumer spending, see us going back to business as usual, that is, expanding the homeownership rate, and building as many large houses as the market will allow. New Urbanists, on the other hand, see the recession as a wake-up call and foresee a return to denser communities. Others see the increase in rental housing as a harbinger of a new Age of Tenants. Advocates of small houses see, well, more small houses. The problem is that most of this is wishful thinking; the truth is that we don’t know whether the housing recession was a correction or a game-changer. My own guess is that Americans’ appetite for large single-family houses on their own lots will not diminish. At the same time, the willingness to take risks will be curtailed, and I would expect that ex-urban housing, far from city centers will be less attractive, in lieu of infill housing in established communities. A lot will depend on how quickly the economy recovers. If high unemployment and low wages drag on for another five years, that will mean that many young families will have been tenants for a full decade—that’s long enough to break the homeownership habit, especially if you can’t afford it anyway. But that’s only a guess.

Levittown, NY, 1948

On the Potomac

by Witold | Nov 17, 2012 | Design

Last week I had the opportunity to sail on San Francisco Bay on the Potomac. The USS Potomac, built as the Coast Guard cutter Electra in 1934, two years later was commissioned as Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s presidential yacht. Roosevelt used it to sail up and down the Potomac until his death in 1945, when the ship was decommissioned. Subsequently, the Potomac had a checkered career. She was used as a ferry boat in the Caribbean, was briefly owned by Elvis Presley, was later used for drug smuggling and seized by the Customs Service, and finally ingloriously sank while at anchor at Treasure Island in San Francisco Bay. She is now owned by the Port of Oakland. The fully restored interior is much as FDR and his many guests, who included George VI and the future Queen Elizabeth, would have known it. The wheelchair-bound President had a rope-powered elevator installed that allowed him to pull himself up to the upper deck, and emerge through a door in the fake second funnel. What is touching is the unpretentiousness of it all; wicker chairs, a modest bunk in FDR’s cabin, and a broad settee in the stern where he could sprawl at presidential ease.

Real and Unreal

by Witold | Nov 8, 2012 | Architecture

The French sculptor, Auguste Rodin, spent the last 24 years of his life living in La Villa de Brillants, his rather grand estate in Meudon, outside Paris. Rodin collected antiquities, and one of his largest possessions was a freestanding section of façade of a seventeenth-century chateau that he had disassembled and moved from nearby Issy-les-Moulineux to his garden. In the 1920s, when Paul Cret was designing a museum in downtown Philadelphia to house Jules E. Mastbaum’s collection of Rodin sculptures, he incorporated a replica of the chateau façade into his design. (Mastbaum, the developer of a chain of movie houses, knew Rodin and had visited Meudon.) The freestanding section of façade forms an entryway into the Rodin Museum grounds, and after crossing the garden, designed by Jacques Gréber, one arrives at the museum itself and a portico dominated by the splendid Gates of Hell. When I visited the recently renovated museum, it struck me that Cret and Mastbaum’s masterly strategy of using a replica to evoke the spirit of Rodin might have informed the design of the new Barnes Foundation, which stands next door. The memory of the old Barnes in suburban Merion, a building that also happened to be designed by Cret, might have been allowed to affect the design of the new Barnes, not only on the interior (as the law required) but also on the exterior. Instead, we have a fussily clad masonry box surmounted by an ungainly glass construction. But more on the New Barnes later.

The Odd Couple

by Witold | Oct 30, 2012 | Design

Norman Bel Geddes (1893-1958) is the subject of a new book. We don’t associate Bel Geddes with iconic designs, as we do his contemporaries such as Walter Dorwin Teague (the Kodak Brownie), Raymond Loewy (the International Harvester tractor), Henry Dreyfuss (the classic Bell telephone handset), or Eliot Noyes (the IBM Selectric typewriter). Rather, Bel Geddes is best remembered for his visionary sci-fi designs, and for popularizing the streamlined style. He has been criticized for indiscriminately streamlining radios and refrigerators as well as buses and cars, although this does not seem any different than architects giving décor or chairs the Bauhaus—or the Baroque—treatment. Bel Geddes was famously responsible for the Futurama exhibit in the General Motors pavilion at the 1939 New York World’s Fair. Less known is that one of the people who worked for him on the design of the building was a young Eero Saarinen. As Jeffrey L. Meikle points out in his interesting essay in the book, Bel Geddes’s extravagant brand of “commercial modernism” (as opposed to functional modernism) was an important influence on Saarinen’s later work. Another influence: Bel Geddes pioneered the public image of the high-profile designer that would become a later fixture in the architectural world. Saarinen learnt from that, too.

Hand and Eye

by Witold | Oct 18, 2012 | Architects, Architecture, Design

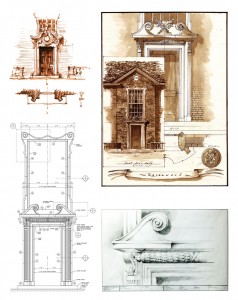

During a recent lecture, Princeton architecture grad Richard Wilson Cameron talked about how he designed Ravenwood, an estate in Chester County, Pennsylvania belonging to the film director, M. Night Shyamalan. What turned into a five-year project involved transforming a rather nondescript Federal Revival house of the 1930s into a lovely Lutyenesque complex of buildings. The high quality of the craftsmanship, both inside and out, is impressive, but equally impressive is Cameron’s working method. According to the website of his firm, Atelier & Co., “We work closely with clients and draw every concept of our projects by hand—from initial sketches and renderings to fully developed design drawings. While we employ digital techniques in our work they are always secondary to our hand drawings.” During his talk, Cameron showed the development of the main entrance to Ravenwood: preliminary sketch, analytique, detail, and construction drawing. The finished product, with a raven sculpted by Foster Reeve, shows the happy result of this traditional working method. The free hand, guided by the eye, has served architects for more than two millennia. The shapes thus produced, whether they are traditional—as here—or modernist, have a distinctly humanist appeal that the machine cannot match.

Firms and Firms

by Witold | Oct 12, 2012 | Architects, Architecture

I was recently asked by the chairman of a real estate company that manages a 4.5 million-square-foot portfolio of retail, office, and industrial properties, if I could recommend a firm to design a new office complex. He wanted a cut above the run-of-the-mill. Running names through my head, I found that almost all of the architects that my Ivy League colleagues and their students admire, the academic A-list so to speak, lack the experience and the staff to tackle a large commercial project. Their reputations are based on institutional rather than commercial projects, campus buildings, museums, and libraries, not on office buildings and shopping malls. While some condo developers did hire boutique firms to produce unusual designs during the last real estate boom, I’m not sure that’s what was required here. “I want my architect to have already made all his mistakes,” a developer friend once told me.

300 New Jersey Avenue, Washington, D.C.

Another alternative is the very large national firms that have branch offices all over the country, and the manpower to tackle any sort of project. Office size is not necessarily a deterrent to quality. A hundred years ago, the best large firms such as McKim, Mead & White, Warren & Wetmore, and Graham, Anderson, Probst & White, capably designed all sorts of buildings—residences, libraries, railroad stations, hotels, apartments, and offices. However, the current large firms resemble architectural widget factories, and can be counted on to produce work that is predictable, glib, and formulaic, without architectural character or conviction. It is unclear to me what is driving this situation. Do the developers demand banal design, or is that what their architects deliver? A spate of well-designed commercial buildings such as 300 New Jersey Avenue, a Washington,D.C. office complex (Rogers Stirk Harbour), the New York Times Building (Renzo Piano Building Workshop), and Tower 4 at the World Trade Center (Maki & Associates)—all designed by foreigners, by the way—suggest that it may be the latter.

THE LATEST

Coming October 8

![GM1939[6]](https://www.witoldrybczynski.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/GM19396-300x190.jpg)