Roundhouses

by Witold | Jan 3, 2013 | Architecture

I recently heard from owner-builder Marvin McConoughey of Corvalis, Oregon, who with his wife built their own house in the 1980s. I was impressed by their ambition (the house is about 2,500 sf), and by their dedication (it took six years). My wife and I spent three years building our own house—which I thought was seriously pushing the limits of both our sanity and our conjugal well-being.

Oh, and the McConoughey house is circular in plan! What is it about round houses that fascinates people? Inigo Jones designed several octagonal houses (although as far as we know he did not build any) and Jefferson built a famous octagonal house at Poplar Forest. McKim Mead & White designed a shingled round house in Jamestown, R.I. One version of Bucky Fuller’s Dymaxion House was hexagonal, another was circular, as were the D-I-Y yurts and dome houses of the 1960s. Today, circular houses are making a small comeback.

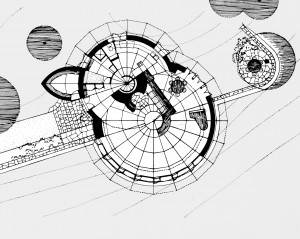

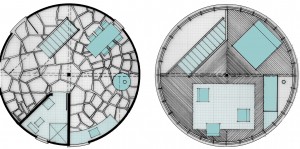

The power of the circle is apparent in a perfectly round space, as architects since Palladio have known. The best round buildings—the Pantheon, the British Museum Reading Room, the Guggenheim Museum—contain such spaces. The challenge of designing a circular house is that once the circle is subdivided into rooms it loses its special quality, and one ends up with awkward spaces that are either pie-shaped or segments of a circle. Wright understood that, which is why he never tried to squeeze a house into a circle, although he used circular shapes (see the Sol Friedman house, two intersecting circles, one subdivided, the other open).

Friedman House, Pleasantville, NY (1948)

In 1967, I, too, had a go. Fresh out of school I designed a circular (20-foot diameter) summer cottage for my parents in Vermont. The solution was prompted by a nearby silo; I planned to use similar curved concrete silo blocks to build the walls. In fact, the two-storey house resembled a silo—or a lighthouse. The lower floor contained the dining area, kitchen, and bathroom, and the upper floor was one big room, with 360-degree views. I never quite figured out the roof—flat or peaked? By then I had realized that since my mother had had polio as a child, a house with a stair was a big mistake. Reluctantly I gave up on the silo and designed a house on one level. It had the shape of a sensible shoebox, and served my parents well for many years.

Ground Floor ……………………..First Floor

Castle is Home

by Witold | Dec 29, 2012 | Architecture

Fonthill Castle, in Doylestown, Pennsylvania, is rarely included among the great country houses of the Gilded Age. This extraordinary house is not designed by an architect, it does not follow one of the accepted styles of the period, and it is just, well, too weird. I can’t think of an American country house that looks like a fortified manor house, not even San Simeon—the closest is Sir Edwin Lutyens’s Castle Drogo in Devon. Fonthill was designed and built between 1908 and 1912 by Henry Chapman Mercer. Like many country-house builders, he used reinforced concrete (cheap and fireproof), but unlike them he used it not only for the walls, but for everything: floors, beams, columns, arches, domes, vaults, roofing, window mullions, even built-in furniture—bookshelves, storage cabinets, and window seats are all concrete. He exploited the plasticity of the material and the result is a curious combination of Antonio Gaudí and the Addams Family. Like his contemporary Gaudí, Mercer (1856-1930) combined concrete with ceramics, made in his own Moravian Pottery and Tile Works (the factory, which resembles a medieval abbey, stands behind the castle). Mercer tiles, inspired by William Morris, were nationally distributed and enliven such buildings as Isabella Stewart Gardner’s Fenway Court and the state capitol in Harrisburg. An Arts and Crafts sensibility permeates Fonthill. The walls, floors and ceilings of the 44 rooms are adorned with tiles and mosaics, and contains his collection of pottery, books, prints, and curios. Well worth a visit; call ahead to confirm times.

Henry Mercer with Rollo

Mercer tile

LEED Lies

by Witold | Dec 26, 2012 | Architecture

7 World Trade Center

Why are so many LEED-certified buildings all-glass? It seemed to defy logic. After all, no matter how much you can reduce artificial lighting by using daylight, the insulation value of glass is negligible compared to solid insulated walls, and anyway there are many overcast days and dark winter afternoons. It is even more puzzling when an all-glass building is shaded. First you wrap it in glass, and then you wrap the glass in something else. I always suspected that this was more about announcing “I am a green building” than about actually conserving energy. And now it’s official. A recent NYT article reported on the results of a New York City study of the actual energy performance of large office towers. (The full report is here.) In the rating system used, 75 is considered the minimum score for a building to be considered “high efficiency.” The all-glass 7 World Trade Center (LEED gold) scored 74, and the Condé Nast Building, highly touted as the city’s first green building when it opened in 1999 received an unspectacular 73. Close but no cigar. Solid buildings with windows, even old ones, do much better: the venerable Empire State scored 80, and Chrysler scored 84. As for the old glass towers, it’s downright embarrassing. The recently renovated Lever House reached only 20, and Seagram scored a miserable 3.

Seasons Greetings

by Witold | Dec 23, 2012 | Architecture

Creche, December 1964 (WR, architect)

Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year to All!

Boiling Water

by Witold | Dec 23, 2012 | Design, Modern life

Every morning I boil water for making tea or coffee (I alternate). What starts my day is the most perfect kettle I have ever used. It is the work of Sori Yanagi (1915-2011), a Japanese product designer probably best remembered for his molded plywood Butterfly Stool. Yanagi studied architecture, but the kettle is decidedly not architectural—no purist Platonic forms, no postmodern irony, no gimmicky whistles. It is just a kettle: handle, spout, lid. Yet this perfectly balanced and shaped everyday object provides a feeling of well-being every time I use it—or even glance at it. In some ways, the deceptively simple kettle, half a million of which are sold annually in Japan, is a distillation of Yanagi’s design philosophy: he was 79 when he designed it.

Like Father, Like Son

by Witold | Dec 21, 2012 | Architects

In an idle moment, I made a list of celebrated architectural dynasties. There are many examples in the past, when knowledge was passed down informally from father to son:

Bartolomeo Sanmicheli and his brother Giovanni and his son Micheli

Andrea Palladio and his son Silla

François Mansart and his grandnephew Jules Hardouin-Mansart

Jacques V. Gabriel and his son Ange-Jacques

William Adam and his sons Robert and John

James Wyatt and his sons Benjamin Dean and Philip

Sir George Gilbert Scott and his son George Gilbert Jr. and his son Sir Giles Gilbert

Samuel Pepys Cockerell and his son Charles Robert and his son Frederick Pepys

Sir Charles Barry and his son Sir John

Benjamin Henry Latrobe and his son Henry

Richard Upjohn and his son Richard M. and his son Hobart

The practice has continued in modern times:

Frank Lloyd Wright and his sons John Lloyd and Lloyd

Eliel Saarinen and his son Eero

Albert Speer and his son Albert

Richard Neutra and his son Dion

Carlo Scarpa and his son Tobia

Emery Roth and his sons Julian and Richard

Edward Durrel Stone and his son Hicks

I.M. Pei and his sons Chien Chung and Li Chung

Cesar Pelli and his son Rafael

Quinlan Terry and his son Francis

Glenn Murcutt and his son Nick

Hugh Newell Jacobsen and his son Simon

It’s a surprisingly long list. Or, maybe, not surprising—growing up with an architect father must create a heightened sense of one’s surroundings. In some cases the father’s reputation dominates, in others the son’s. Robert Adam outshone his father, Henry Latrobe didn’t. In several cases—the Barrys, the Saarinens, the Scarpas—both generations achieved renown. Sir Giles Gilbert Scott, who designed the classic (and classical) British red telephone box, had a not-so-famous architect-father, and a very famous architect-grandfather. In quite a few of the modern cases, given current longevity, father and son work together (Pei, Pelli, Terry, Jacobsen). The name recognition helps, too, of course.

The DD Virus

by Witold | Dec 17, 2012 | Modern life

Last week, after lunch at a bistro on Rittenhouse Square, I dropped in at the Comcast Center to look at the huge video screen—a digital mural—in the lobby. I had written about the screen two years ago, finding it captivating, and since the content regularly changes, I thought it would be fun to see it again. I watched for a while and found my attention wandering. The material seemed less creative, less witty and sophisticated, more predictable. Apart from an interminable clip of close-ups of baseball players in action, the segments seemed shorter, too. Then it dawned on me. The Comcast wall had succumbed to the DD virus. It had been Dumbed Down.

DD is a pernicious modern malady that, sooner or later, seems to affect everything. The New York Times has certainly caught the bug; Arts & Leisure now means less art and more leisure. The PBS News Hour, once challenging with Robert McNeil, Jim Lehrer, and the redoubtable Charlayne Hunter-Gault, has become flabby and predictable. Masterpiece Theater, home to “Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy,” and “Brideshead Revisited” now broadcasts bromides like “Downton Abbey.” As for architecture, can one really imagine that a Louis Kahn—or a Robert Venturi—would be able to break through today?

Modernism the Good

by Witold | Dec 14, 2012 | Architecture

I’ve been reading David Watkin’s Morality and Architecture and I’m struck by the parallel that he draws between modernism and totalitarianism. Now, the conventional story, told and re-told by advocates of the International Style, was that modernist architecture was a moral force, not only opposed to (bad) nineteenth-century Beaux Arts architecture, but also to Nazism and Fascism. This claim was lent credence by the fact that so many leading modernists—Walter Gropius, Mies van der Rohe, Eric Mendelsohn, Marcel Breuer—had fled Nazi Germany. That Le Corbusier happily offered his services to the rightist Vichy regime in France, that Philip Johnson was sympathetic to the National Socialists, and that Mussolini’s Italy sponsored some excellent modernist architecture, did not tarnish the story. Modernism was on the right side: progressive, transparent, clean, unsullied by history. Watkin writes that, quite the opposite, collectivist modernism had a deep totalitarian streak. “The individual is losing significance,” Mies wrote in 1924, “his destiny is no longer what interests us.” Le Corbusier, that other great figure of modernism, likewise saw an impersonal future where houses would be machines for living in. “The denial of the role of the individual as a creative or significant force, and the belief that his role is that of a mere voice through which the great unconscious consensus of the age can be expressed, are ideas familiar in nineteenth- and twentieth century political philosophy,” Watkin writes. Of course, the early modernists were architects not philosophers, and like so many architects they were primarily interested in getting their own way, so much of the deterministic appeal to the zeitgeist was little more than ex post facto rationalization. But isn’t that always the way with architectural theory?

Cinematic Spaces

by Witold | Dec 10, 2012 | Architecture

Roman Polanski and Lindisfarne Castle

Last week I re-watched Roman Polanski’s 1966 film Cul-de-Sac. Lionel Stander and Donald Pleasance are first-rate, but they share star billing with Lindisfarne Castle, which is the location of this one-setting film. Lindisfarne is a sixteenth-century castle that was restored and converted into a country retreat by Sir Edwin Lutyens, whose austere architecture contributes greatly to the tense atmosphere of the film. It reminded me how few movie director’s have exploited outstanding architecture. Joseph Losey set his version of Mozart’s Don Giovanni (1979) in and around Vicenza, and made full use of Palladio’s Villa Rotonda. Jean Luc Godard set Contempt (1963) almost entirely in Curzio Malaparte’s remarkable seaside villa in Capri. Country houses obviously play a big role in British costume dramas: Vanbrugh’s Castle Howard in the original Brideshead Revisted TV series, and Charles Barry’s Highclere Castle in Downton Abbey. But mostly, architecture is merely a walk-on. Hal Ashby gave Richard Morris Hunt’s Biltmore House a cameo role in Being There (1979), although he moved it from Asheville to the outskirts of Washington, D.C. Michelangelo Antonioni, who was trained as an architect, often used modern architecture to convey urban angst, never more than in Zabriskie Point (1970), in which he “blew up” a house designed by Paulo Soleri (in his Wrightian phase). And Stanley Kubrick staged the infamous home invasion scene in A Clockwork Orange (1971) in a coolly modern house designed by Richard Rogers and Norman Foster. Polanski made excellent use of architecture again in The Ghost Writer (2010). The beach house was entirely make-believe—an amalgam of an actual house on Germany’s North Sea coast with shooting sets—but it conveys the slightly spooky atmosphere of elegant, high-end minimalism to a tee.

Kahn’t Do It

by Witold | Dec 9, 2012 | Architecture, Urbanism

A photograph by New York Times photographer Bruce Buck accompanies an article on the wonderful renovation of the Yale University Art Gallery. The gallery was built in three stages: a tall 1866 Ruskinian Gothic first phase by Peter Bonnett Wight (right); a 1928 Florentine Gothic horizontal portion by Egerton Swartwout; and a 1953 addition by Louis Kahn. What Buck’s photo clearly shows is the insensitivity of Kahn’s addition. It is not a question of style—Swartwout did not follow Wight’s lead either—but of massing. The Swartwout wing was rudely truncated by a brick party wall, and was obviously intended to be completed at some future date. Not only does Kahn not complete the work of his fellow architect, he insensitively pulls back to reveal the utilitarian party wall, leaving Swartwout with his metaphorical pants down. In addition, the cavity along Chapel Street does nothing to balance the composition, and only accentuates the difference between Kahn and Swartwout’s buildings—as it was presumably intended to do.

THE LATEST

Coming October 8