Mike’s Place

by Witold | Feb 10, 2013 | Urbanism

Bloomberg Place is a commercial development under construction in central London. The two wedged-shaped office buildings, linked by sky bridges, are designed by Foster + Partners, which is also responsible for the lumpy building next door. What is interesting about Bloomberg Place is its height: ten stories, since this part of the city has a fifty-meter height limit. Washingtonians, currently engaged in a debate over raising the long-time height limit in that city should take note.

Plus ca change

by Witold | Feb 6, 2013 | Housing

The British architect for this amazingly insensitive addition is called Bureau de Change. Need one say more?

The Fourth Man

by Witold | Feb 5, 2013 | Architects

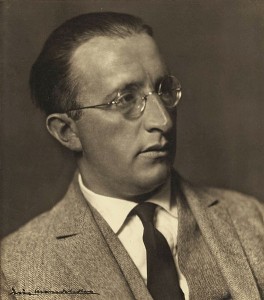

A recent documentary film on the Erich Mendelsohn (1887-1953), Incessant Visions, is a reminder of how history has treated the great architect: not well. He is best rememberd today for the idiosyncratic Einstein Tower in Potsdam, and for a series of expressionistic sketches that he drew while a soldier on the Russian front during the First World War. Yet he was by far the most productive—and the most technologically inventive—of the early modern pioneers (he was born the same year as Le Corbusier), building houses, department stores, synagogues, factories, and a cinema. If his early work is not better known, it is because much of it was destroyed during the Second World War (and in postwar reconstruction), and surviving buildings in East German, Poland, and the Soviet Union were long rendered inaccessible by the Iron Curtain. Moreover, since his architecture didn’t fit the prescribed confines of the International Style, historian/propagandists such as Sigfried Giedion, wrote him out of the story. Yet he belongs in the first ranks of the heroic age of the modern movement, alongside Mies, Corbu, and Gropius. The German phase of Mendelsohn’s career was cut short in 1933 when he fled the Nazis’ persecution of Jews. He subsequently settled in Britain (where he built three striking buildings with Serge Chermayeff), moved on to Palestine, where he built a house for Chaim Weitzmann and hospitals in Haifa and Jerusalem, and spent the last ten years of his life in San Francisco, teaching at Berkeley, and building. Always building.

Schocken Department Store, Chemnitz, 1930

Architect Laureate

by Witold | Feb 4, 2013 | Architecture

The United States has had a poet laureate since 1937. Why don’t we have an architect laureate? An architect laureate could be responsible for advising on important national monuments and memorials, or on makeovers of the Oval Office. The U.S. poet laureate is appointed by Congress, so an architect laureate might have advised congress to be a little more restrained in the $621 million Capitol Visitor Center, or perhaps referee the Eisenhower Memorial imbroglio. But I doubt Congress would look favorably on such a position. After all, building buildings costs money, poets are cheaper (currently $35,000 a year).

Norten’s Taste

by Witold | Jan 31, 2013 | Architects, Architecture

Museo Amparo, Puebla

I attended a public lecture by my friend Enrique Norten last night. He described recent work: a museum in Puebla, a business school for Rutgers, and a city hall in Acapulco—all three competition winners, and all three under construction. All are impressive buildings in different ways. The museum is an addition shoe-horned into a historic complex of buildings, the university building is a self-conscious icon for a re-planned campus, and the capitol is an imaginative exercise in energy conservation. But what struck me is what he did not talk about, but which seemed to me an important aspect of his work: his Taste. Norten’s architecture falls into the category of lightweight construction, and brings to mind Renzo Piano, although it appears less studied and less obsessively detailed. And Piano’s friendly designs can be so unthreatening as to be almost ingratiating, while Norten is never cuddly, and can be downright standoffish in a stylish contemporary way. The architectural equivalent of his five o’clock shadow. His approach to design is to solve problems, a quality he shares with Norman Foster. But while the latter’s work has become increasingly polished, Norten’s taste remains that of an ascetic. A Mexican Zumthor, one might say, a diligent craftsman, though without the Swiss architect’s preciousness, and working on a larger canvas.

Nicknames

by Witold | Jan 27, 2013 | Modern life

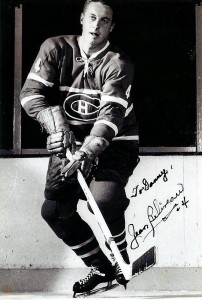

I was in Montreal recently and read in the local paper about the first Canadiens hockey game of the season, which was opened by Jean Beliveau (now 82). In his playing days, Beliveau was known as “Le Gros Bill,” after a popular 1949 French Canadian movie of the same name. Many top hockey players had nicknames: Maurice “Rocket” Richard, Bernard “Boom Boom” Geoffrion, Emile “Butch” Bouchard. The great Jacques Plante was “Jake the Snake.” Nicknames used to be popular. Actors had them, especially the old Western stars—George “Gabby” Hayes, Allan “Rocky” Lane, Alfred “Lash” LaRue, Edmund “Hoot” Gibson, Charles “Buck” Jones, and Woodward “Tex” Ritter, one of the many singing cowboys. Mainstream Hollywood stars used their full first names—Robert, John, James. Today shortened first names are common: Al Pacino, Johnnie Depp, Matt Damon, Tom Hanks. Are nicknames out of fashion? It would seem so. We haven’t had a president with a nickname since Ike, although we’ve had folksy Jimmy and Bill, and we almost had President Al. The last holdout for using nicknames is the Mafia: Andrew “Mush” Russo, Guiseppe “Pooch” Destefano, Joseph “Junior Lollipops” Carna. Some traditions never die.

Playing Games

by Witold | Jan 18, 2013 | Architecture

University of Queensland architecture students, c.1960.

Architectural education differs from other creative fields: art students paint, ceramics students throw pots, film students film, but architecture students can’t build, they can only design. Nevertheless, ever since the Ecole des Beaux-Arts instituted the atelier system, the design studio has dominated architectural teaching. Never mind that this simulation of practice is actually very limited: there is no client, sometimes not even a site, programs are simplified, cost is rarely discussed, and construction is accorded a back seat. Moreover, design juries are generally composed exclusively of architects, rarely are engineers, developers, or lay people included. Little wonder that architects become accustomed to treating design as if it could be isolated from the outside world.

Nutt’s Folly

by Witold | Jan 15, 2013 | Architecture

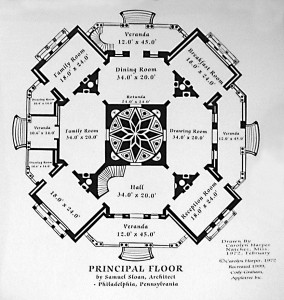

An architect friend reminded me of an extraordinary octagonal house in Natchez, Mississippi. Longwood was built just before the Civil War for Dr. Haller Nutt, a cotton planter, by the Philadelphia architect, Samuel Sloan. Construction was interrupted by the war (the Philadelphia craftsmen simply went home), and after Nutt’s death in 1864 construction stopped altogether. Although the brick shell and verandas were completed, only the basement was ever finished inside. Sloan’s plan is remarkable, since by the judicious placement of the verandas he manages to create two ranges of rooms (there were to be 32 rooms in all). The central space is top lit by the onion-domed cupola, making this a distant cousin of Palladio’s Villa Rotonda, although the architecture is not classical but Byzantine-Moorish—or something.

Schooldays

by Witold | Jan 5, 2013 | Design, Modern life

An article in today’s New York Times on classroom chairs reminded me of my schooldays. As far as I remember, we had wooden desks with a built in bench seats, attached to the floor. The desk-top, usually carved with a chronicle of interesting graffiti, was sometimes hinged with a storage space beneath that we never used. We didn’t used the hole in the top, which was made to hold an ink-well, either. The desks were sturdy and not particularly comfortable—they weren’t intended to be. The Times piece is full of fluff about how different classroom chairs might improve learning, although the author allows that New York City’s Model 114 stacking chair has its defenders. “But is some quarters, the chair and others like it are seen as stubborn holdovers from before the age of ergonomics, when American schools’ main job was to turn out upright citizens, and rote learning was the student’s lot.” Since most people agree that American education has declined precipitously since the Age of Rote Learning, I wonder if a “stubborn holdover” is really so bad.

Roundhouses

by Witold | Jan 3, 2013 | Architecture

I recently heard from owner-builder Marvin McConoughey of Corvalis, Oregon, who with his wife built their own house in the 1980s. I was impressed by their ambition (the house is about 2,500 sf), and by their dedication (it took six years). My wife and I spent three years building our own house—which I thought was seriously pushing the limits of both our sanity and our conjugal well-being.

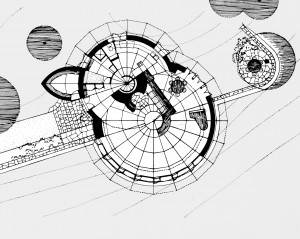

Oh, and the McConoughey house is circular in plan! What is it about round houses that fascinates people? Inigo Jones designed several octagonal houses (although as far as we know he did not build any) and Jefferson built a famous octagonal house at Poplar Forest. McKim Mead & White designed a shingled round house in Jamestown, R.I. One version of Bucky Fuller’s Dymaxion House was hexagonal, another was circular, as were the D-I-Y yurts and dome houses of the 1960s. Today, circular houses are making a small comeback.

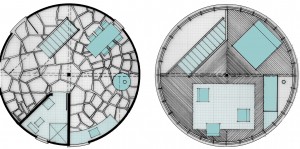

The power of the circle is apparent in a perfectly round space, as architects since Palladio have known. The best round buildings—the Pantheon, the British Museum Reading Room, the Guggenheim Museum—contain such spaces. The challenge of designing a circular house is that once the circle is subdivided into rooms it loses its special quality, and one ends up with awkward spaces that are either pie-shaped or segments of a circle. Wright understood that, which is why he never tried to squeeze a house into a circle, although he used circular shapes (see the Sol Friedman house, two intersecting circles, one subdivided, the other open).

Friedman House, Pleasantville, NY (1948)

In 1967, I, too, had a go. Fresh out of school I designed a circular (20-foot diameter) summer cottage for my parents in Vermont. The solution was prompted by a nearby silo; I planned to use similar curved concrete silo blocks to build the walls. In fact, the two-storey house resembled a silo—or a lighthouse. The lower floor contained the dining area, kitchen, and bathroom, and the upper floor was one big room, with 360-degree views. I never quite figured out the roof—flat or peaked? By then I had realized that since my mother had had polio as a child, a house with a stair was a big mistake. Reluctantly I gave up on the silo and designed a house on one level. It had the shape of a sensible shoebox, and served my parents well for many years.

Ground Floor ……………………..First Floor

THE LATEST

Coming October 8