Big John

by Witold | Apr 2, 2013 | Architecture

I was in Chicago recently for the Driehaus Prize ceremony, and I was staying in a hotel across North Michigan Avenue from the John Hancock Center, in fact my fortieth-floor room looked directly at the building. Built in 1969, and designed by Bruce Graham and Fazlur Khan of Skidmore Owings & Merrill, this has always been one of my favorite Chicago skyscrapers. The characteristic tapered silhouette is much more successful than the Sears Tower (another Graham-Khan collaboration), and the crisscrossing bracing remains an evocative expression of its structure. I could see Mies’s 860 Lake Shore Drive from my hotel room, and the Hancock tower seemed like a perfect hommage to the master, yet making its own way. I had always seen Hancock from a distance, or from the street, but never from this vantage point. I must confess to being disappointed. The matte black curtain wall appeared crude. The heavy diagonal braces were crude too, not just in execution but in the way they relentlessly enclosed the Miesian curtain wall in a clumsy corset. You could argue that the Hancock Center was not meant to be seen close-up. Yet immediately next to it is Holabird & Root’s Palmolive Building (1930), topped by the Lindbergh Beacon. This early example of a moderne style presents a lively and articulated mass that rewards close inspection. There is something appealing—dare I say humanist?—about Holabird & Root’s delicately articulated skyscraper, in contrast to its burly and somewhat intimidating neighbor.

The White City

by Witold | Mar 30, 2013 | Architecture, Urbanism

K Street, Washington, DC

During the last decade or so, Washington, D.C. has undergone a little-noticed but remarkable transformation: a city of stone is becoming a city of glass. Ever since the McMillan Plan, and even before, important civic buildings in the capital were built out of marble, limestone, or concrete. There were a few early brick outliers such as the Smithsonian Castle, and the Pensions building, but generally architects followed this custom. This was not a question of style, since modernist as well as postmodernist architects—Breuer, Bunshaft, Pei, Stone, Obata, Erickson, Graves, Freed—all followed the age-old practice, which had been virtually codified by Burnham, McKim and company in the early 1900s. This materials choice, not confined to government buildings, gave the city a pleasant uniformity. Today, the capital is quickly becoming a city not of masonry, but of glass. With the notable exception of Moshe Safdie’s Institute of Peace and Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives headquarters (both precast concrete), federal and commercial buildings have adopted glass as the new lingua franca. And precast concrete buildings of the 1960s are being retrofitted with glass curtain walls. This architectural fashion is not confined to DC, but it is more striking there given the city’s predominant neoclassic fabric. The new city has a somewhat schizophrenic appearance, since the transparency of the glass is contradicted by rings of security devices: screening pavilions, guardhouses, Delta barriers, and rings and rings of bollards.

Driehausville

by Witold | Mar 25, 2013 | Architecture

Carl Laubin has painted a beautiful capriccio to commemorate the tenth anniversary of the Richard H. Driehaus Prize. He portrays an imaginary town made up of the works of the first ten Driehaus laureates, among whom are Léon Krier, Quinlan Terry, and Demetri Porphyrios, as well as Allan Greenberg, Jaquelin T. Robertson, and Michael Graves. In the foreground is the Choragic Monument of Lysicrates, a bronze miniature of which is presented to each laureate. It’s fun to try and identify the individual works in this large (5½ by over 8 feet long) painting. But what is more striking is that Laubin has created a convincing urban landscape solely out of landmark buildings. That, of course, is the advantage of classicism: however it is interpreted, it is a tradition that manages to produce a more or less coherent whole. Even Abdel-Wahed El Wakil’s mosque, standing next to a Seaside beach house by Robert A. M. Stern, doesn’t look too out of place. Can one imagine a similar townscape of Pritzker Prize winners? Well, maybe with the work of some of the early laureates—Pei, Bunshaft, Tange, Siza—but modern buildings need a background of nineteenth and early twentieth century urbanism to shine. A town made up of only signature buildings by our current generation of stars would resemble a carnival or a theme park—Pritzkerland.

There is a discussion of the Driehaus Prize and a larger image of Laubin’s painting here.

Hitler’s Architect

by Witold | Mar 21, 2013 | Architects

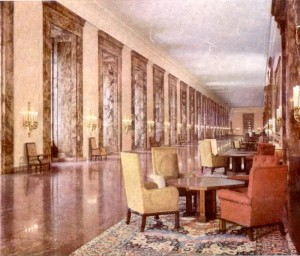

In 1985 Léon Krier published Albert Speer: Architecture 1932-1942, a monograph on the work of Hitler’s architect. The book, assembled with Speer’s assistance, was received with almost universal opprobrium, Krier was vilified, Speer’s version of classicism was ridiculed, the whole thing written off a sick joke. Now, almost thirty years later, Monacelli has produced a facsimile edition of the book, together with new material by Krier and a foreword by Robert A. M. Stern. Perhaps this time the reception will be different, but I doubt it. Speer’s brand of stripped classicism is so much associated with Nazism, and modernist ideologues have done such a good job of ensuring that this is so, that it is hard to evaluate the work objectively. Never mind that the architecture adopted by the Nazi regime is not therefore Nazi architecture—the stripped classicism, or New Classicism as its chief proponent Paul Cret called it, was a perfectly respectable style of that period. And never mind, as Krier points out, that other aspects of the Nazi regime—Leicas, Volkswagens, autobahns, rocketry—have easily shed their National Socialist roots. But if you are able, take a long hard look at Speer’s work, handsomely reproduced in photos, drawings and models, both architecture and urbanism. You may not agree with Krier that Speer was “one of the most famous architects of the twentieth century,” but it’s hard to deny him a leading position alongside such master of monumental classicism as Cret, John Russell Pope, and Gunnar Asplund. The Neue Reichskanzlei (demolished by the Soviets) in particular is a remarkable piece of work, inside and out.

Neue Reichskanzlei, Marble Gallery, 1938

Day One

by Witold | Mar 14, 2013 | Architecture

High Hollow, George Howe, arch., 1917

I live in a neighborhood with many old houses. There are plenty of late nineteenth-century examples, but the ones I like best are from 1900-1930. The acknowledged masterpiece of this period is George Howe’s High Hollow, but there are plenty of runners-up, the work of accomplished Philadelphia residential architects such as Wilson Eyre, Frank Miles Day, Robert Rodes McGoodwin, H. Louis Duhring, and Edmund Gilchrist. These old houses seem to improve with age—the slate roofs get a bit mossy, the stonework acquires a patina, and the heavy hardware gets burnished with use. Their architects worked in more or less revival styles, and because they acknowledged the past, the passage of time has been kind to their creations. Indeed, these houses probably look better today than when they were spanking new. In contrast, the handful of mid-twentieth-century works by Louis Kahn, Robert Venturi, and Romaldo Guirgola, seem embalmed, caught in the moment of their construction. It is not just a question of materials, although smooth stucco tends to weather poorly, and tar-and-gravel roofs don’t age gracefully. It has to do with their disconnection from history. Modern houses look their best on Day One, when they are new, fresh, unsullied by use or time. It is all downhill after that.

Esherick House, Louis Kahn, arch., 1959

No Hoopla

by Witold | Mar 9, 2013 | Architects, Architecture

Photograph: Raymond Meier/Vanity Fair

Much has been written about the recently completed FDR Memorial in New York, designed by Louis Kahn. It was the great architect’s last project, and he had just completed it when he died in 1974, almost four decades ago. Kahn’s design reminds us how much has changed in forty years. First, the commission was not the result of a competition, no hoopla, no wowing the jury, no rush. Instead Kahn was given the time to ponder and reflect—which is how he worked, anyway. Second, although the site covers about three and a half acres on the tip of Roosevelt Island, the memorial itself is an open-air room, only sixty feet square; Kahn felt no need to spread over the entire site, treating the rest instead as a green forecourt. The room is close in spirit to the commemorative block of marble that FDR’s friends erected in front of the National Archives in Washington, DC. Third, the memorial is not only small in size, it is focused. A single quotation (the famous Four Freedoms speech) and the president’s name, are all the writing there is; no didactic explanations, no rhetoric, no wheel chair, no Fala. Fourth, Kahn recognized that a memorial to a person must include that person’s presence, here in the form of a bust by Jo Davidson. All important lessons for future memorial builders.

Urban Topos

by Witold | Mar 4, 2013 | Urbanism

Vancouver, BC

There are many ways to measure cities: population, unemployment, crime rates, pollution, literacy rates, and so on. Aesthetics is harder to quantify, and so it is easier to ignore, yet beauty is also an important urban variable. Beauty in the manmade environment takes the form of streets, squares, and buildings, so it is tempting for cities to seek improvements in the urban equivalent of facelifts and makeovers: new boulevards, parks, civic monuments. But there is a type of urban beauty that is harder to improve: the natural setting. Cities on islands (New York, Stockholm) have a sort of self-contained magic. Cities with hills (Montreal, Rome) feel as if they are tied to something elemental. Rivers used to be an indispensible attribute for a thriving city, but today they are purely an amenity. A city with an attractive river (Paris, London, Prague)—not too large and not too small—gains not only river walks. Crossing a bridge in a city feels like a temporary natural reprieve. That’s why lovers meet on bridges. The presence of water is always nice, even when its manmade (Venice, St. Petersburg) but not all water is created equal; there is nothing like the view of a beautiful bay (San Francisco, Rio de Janeiro) to spice up the urban scene. Views of majestic mountains (Seattle, Vancouver) are almost as good—plus they mean nearby skiing and hiking. There are inland cities on flat sites without charming rivers or mountain views (Houston, Beijing, New Delhi) that have overcome the lack of a beautiful setting. But the cities with beautiful natural settings will always have a leg up.

Leaky Jim

by Witold | Mar 1, 2013 | Architects

In a history of postmodernism (history written on the fly since the book was published in 1984) Heinrich Klotz wrote: “James Stirling has received only one commission in his own country since he made his change to postmodernism, yet what stands in the way of postmodernism in Great Britain is not so much a lack of commissions as a continuing faith in modernism.” As evidence, Klotz cited the successes of Norman Foster, Ove Arup, and Richard Rogers. The persistence of modernism in Britain in the eighties was undoubted, but Stirling’s lack of commissions was due to something else. The trio of red-brick university buildings that launched his career—the University of Leicester Engineering Building, the History Faculty and Library at Cambridge, and the residential Florey Building at Queen’s College, Oxford, were aesthetic successes but rather spectacular technical failures. The glass roofs leaked, both in the engineering building and the library (!), and the heavily glazed spaces were impossibly cold in the winter. In an AD profile of the Florey Building, an ex-resident reminisced about his student days: “The Florey Building was an unmitigated disaster to live in. The arrangement of rooms meant that privacy was only achievable by drawing down blinds, and the aluminum strips connecting windows to walls conducted sound so that one could easily hear conversations in the next room.” Indeed, Florey had so many problems that the university brought a law suit against Stirling’s firm. According to AD, “As a result, Stirling’s office was unable to find work in England for at least a decade after the Florey building, instead finding promise of work in places like Germany, Japan, and the Unites States.”

Florey Building

An Age of Anxiety

by Witold | Feb 26, 2013 | Modern life

Every evening I watch the evening news. News may not be exactly the right word. The reports are a combination of speculation about what is about to happen—a presidential speech, a new pope, the Oscars—and spokespeople touting one point of view or another on the issue of the day. Which today is sequestration, or rather “what Washington refers to a sequestration,” as the media insists on calling it, despite the fact that by now it is a term surely familiar to all. But perhaps the most common “news” story is the revelation of a new topic of concern: a previously ignored disease, an unnoticed social condition, an overlooked environmental effect, a looming problem. Journalistic careers are made by discovering the next new trouble: on-line privacy, bullying, school soccer injuries, cheating on school tests, whatever. Since the evening news insists on being upbeat–at least on PBS– however dire the problem, it can always be fixed, we are told by the earnest experts. Just once, it would be refreshing to hear that a problem was insoluble. “Sorry, nothing can be done about it. It’s just human nature. We’ll have to learn to live with it.”

Secret History

by Witold | Feb 17, 2013 | Architects, Architecture

If I were compiling a secret history of architecture—those unpedigreed works of genius that stand outside the mainstream—I would include Gaudí, of course, but also many lesser figures: Henry Chapman Mercer, the builder of several amazing concrete structures in Doylestown, Pennsylvania; Paul Chalfin, the creative force behind that ebullient Baroque pile, Vizcaya, in Miami; and Simon Rodia, creator of Watts Towers in LA. I would also have to add my friend, George Holt in Charleston, whose Byzantine concoctions have no contemporary analog. There would also be a number of women in this company: Theodate Pope whose Avon Old Farms School anticipate Hobbits; Mary Elizabeth Jane Colter, who designed the wonderful stone structures that grace the rim of the Grand Canyon; and Sarah Losh, the subject of a new biography by Jenny Unglow. Losh (1786-1853) built little—a country church, a schoolhouse and a sexton’s cottage—but what she did build is exceptional, and exceptionally original. The small church of St. Mary’s in the village of Wreay in the Cumbrian hills, where she lived, anticipates the Romanesque revival, but also includes personal decoration that has no historical antecedents: column capitals in the form of lotus buds; gargoyles in the form of winged turtles; a baptismal font carved (by Losh herself) with floral patterns; and a profusion of pinecones. Quite wonderful

St. Mary’s, Wreay

Baptismal Font

THE LATEST

Coming October 8