GOD’S HOUSE

by Witold | May 21, 2013 | Architecture, Modern life

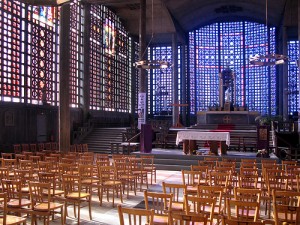

In an article in the current issue of Design Intelligence, the architect and Notre Dame professor, Duncan G. Stroik writes that the design of contemporary megachurches, which he characterizes as “non-architecture,” leaves much to be desired. It’s hard to argue with that (see my Slate slide show on megachurches here). But then Stroik goes on to equate megachurches with modernism, whence he elides into the classicist’s standard litany of the failings of modernist architecture. “Gone was the need for human scale and proportions, natural materials, historical elements, and the classical understanding of civic order,” he writes. I am not sure what he means by “natural materials,” but presumably concrete does not qualify, yet Auguste Perret’s all-concrete Notre-Dame du Raincy, an early classic, is a modern reinterpretation of the Gothic. I don’t know that Gaudi had a classical understanding of civic order, but Sagrada Familia shines with his deep religiosity. So does Fay Jones’s Thorncrown Chapel, which incorporates natural materials and human scale.

Stroik similarly exaggerates when he writes that Wright, Le Corbusier, Aalto and Mies “did very few churches.” It is true that Mies designed only the rather forlorn chapel at IIT, but Le Corbusier built three churches, and Wright built no less than six places of worship: Unity Temple, Unitarian Meeting House, a Greek Orthodox church, Congregation Church, Beth Sholom Synagogue, and a chapel at Florida Southern University. As for Aalto, he designed six churches as well as two funerary chapels (one unbuilt). I have not seen his transcendent church at Imatra, but I have seen Wright’s Beth Sholom, and it is a numinous space. So is the dark cave of Ronchamp. I recently re-visited Bernard Maybeck’s First Church of Christ Scientist in Berkeley. While this exceptional design is hardly a paragon of modernism, neither is it bound by tradition. But it is a moving and much loved place of worship.

I AM A MEMORIAL

by Witold | May 16, 2013 | Architecture, Modern life

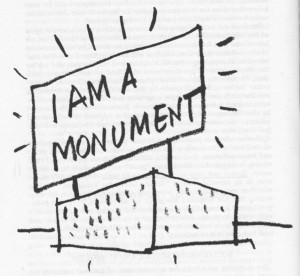

The book launch of Civic Art, a history of the first hundred years of the U.S. Commission of Fine Arts, was the occasion for the Charles Atherton Memorial Lecture at the National Building Museum, delivered this year by Thomas Luebke, the current secretary of the commission. In the course of his talk, Luebke made an interesting observation: commemorative memorials in Washington, D.C. have become increasingly influenced by other media, specifically photography. When the Lincoln Memorial was completed in 1922, Daniel Chester French’s statue of the president was the sculptor’s interpretation of his subject (French did have access to a life mask of Lincoln, as well as plaster casts of his hands), and in due course the seated figure became a national icon. When the Marine Corps Memorial was unveiled in 1954, it consisted of a giant statue based on the AP correspondent Joe Rosenthal’s photograph of Marines raising the flag at Iwo Jima. Instead of creating an original work, the “sculptor,” one Felix de Weldon, simply appropriated an already famous image. The photo, not the memorial, was the real icon. More recent commemorative works, such as the Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial, have been similarly based on photographs. Likewise the current version of the proposed memorial to Dwight D. Eisenhower. Why does this matter? Memorials that simply mimic another medium lose much of their power; they are more like billboards than sacred markers. Robert Venturi once proposed that a civic building should be designed as a simple box with a blinking sign on top saying I AM A MONUMENT. One is never quite sure how seriously to take Venturi’s offbeat pronouncements, but the current crop of photographic-inspired memorials suggests just how thin the joke really is.

The book launch of Civic Art, a history of the first hundred years of the U.S. Commission of Fine Arts, was the occasion for the Charles Atherton Memorial Lecture at the National Building Museum, delivered this year by Thomas Luebke, the current secretary of the commission. In the course of his talk, Luebke made an interesting observation: commemorative memorials in Washington, D.C. have become increasingly influenced by other media, specifically photography. When the Lincoln Memorial was completed in 1922, Daniel Chester French’s statue of the president was the sculptor’s interpretation of his subject (French did have access to a life mask of Lincoln, as well as plaster casts of his hands), and in due course the seated figure became a national icon. When the Marine Corps Memorial was unveiled in 1954, it consisted of a giant statue based on the AP correspondent Joe Rosenthal’s photograph of Marines raising the flag at Iwo Jima. Instead of creating an original work, the “sculptor,” one Felix de Weldon, simply appropriated an already famous image. The photo, not the memorial, was the real icon. More recent commemorative works, such as the Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial, have been similarly based on photographs. Likewise the current version of the proposed memorial to Dwight D. Eisenhower. Why does this matter? Memorials that simply mimic another medium lose much of their power; they are more like billboards than sacred markers. Robert Venturi once proposed that a civic building should be designed as a simple box with a blinking sign on top saying I AM A MONUMENT. One is never quite sure how seriously to take Venturi’s offbeat pronouncements, but the current crop of photographic-inspired memorials suggests just how thin the joke really is.

GREATEST HITS

by Witold | May 13, 2013 | Architecture

Anyone watching “Ten Buildings that Changed America” last night on PBS was challenged to make their own additions or deletions to the list. I must admit that I was surprised to find Jefferson’s Virginia Capitol rather than his University of Virginia, leading the Top Ten, for it was the university that set the model for the bucolic college campus, which is one of America’s great architectural achievements. But the show convinced me that the Capitol, which established Classicism as the de facto government style, deserves to be included. No one would argue with Trinity Church, the Wainwright, or the Robie House. Albert Kahn’s factories for Henry Ford are an outlier, but every Greatest Hits needs a surprise. Seeing the factories is a reminder of how much more advanced in functionalist design America was compared to Europe (the Bauhauslers greatly admired Kahn’s work), although the Prussian-born Kahn wisely restricted his no-frills style to factories. I’m not sure I would have included Saarinen’s Dulles airport, which jumbo jets rendered obsolete within a decade, and whose goofy mobile lounges had few takers. Dulles never had the national influence of, say, Boston’s South Station (Shepley, Ruttan & Coolidge, 1898). And does the Seagram Building really qualify as a building than changed America? Beloved by architects—though not so much by the public—the Seagram was too expensive to be widely influential. And by the time it was built—1958—the gridded steel-and-glass curtain wall was already in widespread use, thanks to Mies’s pioneering 860 Lake Shore Drive apartments. But then the producers could not have included a lively interview with Phyllis Lambert, which would have been a loss.

Stiltsville

by Witold | May 8, 2013 | Urbanism

Beachtown is a New Urbanism second-home village in Galveston. Construction began in 2005, after a protracted planning and permitting period. The projected size is about 2,000 houses. Progress has been slow, but then Galveston is hardly a hot development area. Although only fifty miles from Houston, the city never really recovered from a devastating 1900 hurricane. The hurricane, and the Houston Ship Canal, ensured that Houston prospered while Galveston languished. So building a Texas version of Seaside, even when it is planned by Duany & Plater-Zyberk, is a real estate challenge (I saw only a single house under construction). Equally challenging is the requirement that since Beachtown is immediately adjacent to the beach, all habitable space must be raised above the base flood elevation (BFE). Since Hurricane Ike (2008) had a 15-20 foot storm surge, the BFE is high, and the houses are raised about twelve feet above grade on closely spaced timber piles. The

Beachtown is a New Urbanism second-home village in Galveston. Construction began in 2005, after a protracted planning and permitting period. The projected size is about 2,000 houses. Progress has been slow, but then Galveston is hardly a hot development area. Although only fifty miles from Houston, the city never really recovered from a devastating 1900 hurricane. The hurricane, and the Houston Ship Canal, ensured that Houston prospered while Galveston languished. So building a Texas version of Seaside, even when it is planned by Duany & Plater-Zyberk, is a real estate challenge (I saw only a single house under construction). Equally challenging is the requirement that since Beachtown is immediately adjacent to the beach, all habitable space must be raised above the base flood elevation (BFE). Since Hurricane Ike (2008) had a 15-20 foot storm surge, the BFE is high, and the houses are raised about twelve feet above grade on closely spaced timber piles. The  effect is unusual. While the project has all the features one would expect in a DPZ design—interesting plan, sidewalks, thoughtful planting, pathways—the scale is distinctly different. Instead of cottages, the houses resemble Victorian mansions, in part because this is Texas after all and they are very large, and in part because they are in some cases four-stories tall, thanks to the BFE. As you walk down the street you don’t see friendly porches, only driveways and parking bays. Next to Beachtown is a rather incongruous 14-story condominium tower. Or perhaps it’s not so incongruous. If one insists on living next to the water in such a dangerous location—a dubious proposition—one would want to be in a concrete structure high, high above the flood surge.

effect is unusual. While the project has all the features one would expect in a DPZ design—interesting plan, sidewalks, thoughtful planting, pathways—the scale is distinctly different. Instead of cottages, the houses resemble Victorian mansions, in part because this is Texas after all and they are very large, and in part because they are in some cases four-stories tall, thanks to the BFE. As you walk down the street you don’t see friendly porches, only driveways and parking bays. Next to Beachtown is a rather incongruous 14-story condominium tower. Or perhaps it’s not so incongruous. If one insists on living next to the water in such a dangerous location—a dubious proposition—one would want to be in a concrete structure high, high above the flood surge.

In the Shade

by Witold | May 4, 2013 | Architecture

The vast majority of certified green office buildings today seem to be all-glass. That’s counterintuitive, since glass lets in the sun’s heat. Surely it’s time to revisit one of Le Corbusier’s modernist trademarks, the brise-soleil, or sunshade. Corb’s sunshades tended to be made out of concrete, which is actually the wrong material, since it absorbs the sun’s heat, stores it, then dissipates it long after the sun goes down. But the basic idea is sound: prevent the rays of the sun from entering and heating up the interior of the building. I was reminded of Corb during a recent visit to Houston. There are several downtown office buildings of the sixties and seventies here whose design actually acknowledges the god-awful summers. Pictured here is 1001 Preston Street, designed in 1978 by Kenneth Bentsen, a local practitioner. The ten-story precast concrete frame has a deep facade, à la SOM, and is fitted with metal louvers that act as sun shades. Of course, the newest crop of towers is all-glass. No doubt they have a LEED rating.

The vast majority of certified green office buildings today seem to be all-glass. That’s counterintuitive, since glass lets in the sun’s heat. Surely it’s time to revisit one of Le Corbusier’s modernist trademarks, the brise-soleil, or sunshade. Corb’s sunshades tended to be made out of concrete, which is actually the wrong material, since it absorbs the sun’s heat, stores it, then dissipates it long after the sun goes down. But the basic idea is sound: prevent the rays of the sun from entering and heating up the interior of the building. I was reminded of Corb during a recent visit to Houston. There are several downtown office buildings of the sixties and seventies here whose design actually acknowledges the god-awful summers. Pictured here is 1001 Preston Street, designed in 1978 by Kenneth Bentsen, a local practitioner. The ten-story precast concrete frame has a deep facade, à la SOM, and is fitted with metal louvers that act as sun shades. Of course, the newest crop of towers is all-glass. No doubt they have a LEED rating.

Prez Library

by Witold | Apr 27, 2013 | Architecture

Since I was on the design committee that advised Laura Bush on the George W. Bush presidential library, I am not in a position to offer an objective review of the architecture of the building. You will have to make up your own mind. I suspect many people will do this without actually visiting the building, but when you read the reviews keep several things in mind. Presidential libraries should have an intimate quality since they are, in one measure, personal shrines. The most successful example in this regard is the FDR Library in Hyde Park, NY, a small Dutch colonial building designed by the president himself. But today’s presidential libraries have grown very large (226,000 square feet in Dallas), and the challenge for the architect is how to design a building so that it doesn’t overwhelm the visitor. The LBJ Library in Austin fails in this; LBJ may have been a larger-than-life figure, but Bunshaft’s ponderous design is merely monumental. Scale is all. A presidential “library” actually consists of a museum, a scholarly study center, archives (largely digital, but in the Bush archive, still including 70 million pieces of paper), and here also a think tank/institute, akin to the Hoover Institution at Stanford. So, this unusual building type is also a planning challenge, since these parts function independently: some are public, some are private, some belong to the federal government, some don’t. Since the Bush Center incorporates a public museum and institutional components, as well as the presidential quarters (in this case not lived in, but used for entertaining eminent visitors), the architecture must demonstrate different levels of formality and intimacy. Finally, presidential libraries are there for the long haul. No building is timeless, but the design of a presidential library should not become immediately dated, which favors a conservative approach. While some reviewers have sought to find parallels between Robert A. M. Stern’s design and Mussolini’s Fascist architecture, surely the real model is pre-World War II US government architecture, like Paul Cret’s Federal Reserve Board Building, which was the delicate moment when Classicists adopted a modernist sensibility. New Classicism, Cret called it.

Since I was on the design committee that advised Laura Bush on the George W. Bush presidential library, I am not in a position to offer an objective review of the architecture of the building. You will have to make up your own mind. I suspect many people will do this without actually visiting the building, but when you read the reviews keep several things in mind. Presidential libraries should have an intimate quality since they are, in one measure, personal shrines. The most successful example in this regard is the FDR Library in Hyde Park, NY, a small Dutch colonial building designed by the president himself. But today’s presidential libraries have grown very large (226,000 square feet in Dallas), and the challenge for the architect is how to design a building so that it doesn’t overwhelm the visitor. The LBJ Library in Austin fails in this; LBJ may have been a larger-than-life figure, but Bunshaft’s ponderous design is merely monumental. Scale is all. A presidential “library” actually consists of a museum, a scholarly study center, archives (largely digital, but in the Bush archive, still including 70 million pieces of paper), and here also a think tank/institute, akin to the Hoover Institution at Stanford. So, this unusual building type is also a planning challenge, since these parts function independently: some are public, some are private, some belong to the federal government, some don’t. Since the Bush Center incorporates a public museum and institutional components, as well as the presidential quarters (in this case not lived in, but used for entertaining eminent visitors), the architecture must demonstrate different levels of formality and intimacy. Finally, presidential libraries are there for the long haul. No building is timeless, but the design of a presidential library should not become immediately dated, which favors a conservative approach. While some reviewers have sought to find parallels between Robert A. M. Stern’s design and Mussolini’s Fascist architecture, surely the real model is pre-World War II US government architecture, like Paul Cret’s Federal Reserve Board Building, which was the delicate moment when Classicists adopted a modernist sensibility. New Classicism, Cret called it.

Lest We Forget

by Witold | Apr 23, 2013 | Design, Modern life

We remember the past in different ways. World War II produced memoirs (Frank, Wiesel, Tregaskis), histories (Churchill, Shirer, Keegan), novels (Mailer, Jones, Heller), and innumerable films and television documentaries. So did the Vietnam War (Dispatches, A Rumor of War, A Bright Shining Lie, The Best and the Brightest, as well as The Deerhunter, Apocalypse Now, and Platoon). Of course, there are also built memorials, which form the focus of wreath-layings and commemorative ceremonies, but our memory resides in many places. So I find the present custom of making so-called visitor centers an integral part of memorials odd, not to say redundant. A museum was to be a part of the World War II Memorial in Washington, D.C., but was wisely removed. Less wisely, Congress has approved an underground “education center” next to the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, although that project happily appears stalled. The other night, “Sixty Minutes” showed the 9/11 museum under construction at the World Trade Center site. You would have thought that the vast outdoor memorial would have been sufficient commemoration, but we are also to have a vast underground space devoted to the events of that unhappy day. I once visited the Resistance museum in Oslo, the subject of which was the Norwegian resistance to the Nazi occupation during World War II. It is estimated that 40,000 men and women took an active part in the resistance movement. The museum displays included Sten guns, short-wave radios, and miniature tableaux of wartime scenes, with tiny armored cars being sabotaged, and agents parachuting among cotton-batten clouds. It was informative, charming, and low-key in a laid back Scandinavian sort of way. If we must have a 9/11 museum, I wish it were that modest.

MoMA Mia

by Witold | Apr 20, 2013 | Architecture

I find it hard to believe the stated rationale for the demolition of what had been the home of the American Folk Art Museum on 53rd Street—that its blank façade does not accord with MoMA’s glassy image. I’m not one to defend the inhospitable face that Williams & Tsien’s design turns to the street, but MoMA itself is hardly the most considerate neighbor, as I wrote in Slate shortly after Yoshio Taniguchi’s makeover opened. The truth is that the building whose announced demolition has caused such a furor, at least among architects and architecture critics, is not a very good museum. The idiosyncratic interior—mostly circulation space—with its exciting but distracting views, its multitude of materials, and its busy details, overwhelms whatever is being displayed. This may have been acceptable—just—when the museum was a kind of cabinet of curiosities; it’s hard to imagine it as a place for art.

Detached Retina

by Witold | Apr 15, 2013 | Architects

My friend George Holt and I were talking about how architectural education ill-prepares young architects for the world of practice. “Is this sort of detachment from the realities of the profession a deliberate agenda that’s perhaps for some other useful purpose that escapes me?” George asked me. I don’t think so. In part, the detachment is a legacy of the art school tradition that shaped architecture schools since the Ecole des Beaux-Arts and the Bauhaus. Of course, artists have always worked on commission, too, just like architects, but the unspoken ideal is the self-sufficient artist—Van Gogh, Gauguin, Matisse—whose inspiration was entirely personal. In this view, the outside world of patrons, dealers, museums, and the public is extraneous at best, intrusive at worst. There is also a sense that in the architecture studio the external world should be kept at bay, lest it crimp the imagination of the young tyros, who will learn soon enough, the argument goes, about the realities of practice. Thus, even experienced architects set aside their practical knowledge when they put on their teaching hats, and weave the fairy tale of pure design. And then there is the attractive—if grievously flawed—myth of the architect as outsider, as if buildings, large and expensive, were somehow a vehicle for personal expression rather than a product of societal forces.

Soleri

by Witold | Apr 10, 2013 | Architects

Paolo Soleri died yesterday at 93. I first heard of him when I was a college student. A classmate, Ray Catchpole, had spent the summer at Soleri’s desert compound in Arizona (he had several sand-cast bronze wind bells in his room), and he encouraged me to go if I had the chance. That year—1964—I was editor-in-chief of Asterisk, a student magazine, and it must have been through Ray that we got Soleri to send us an article: “Computer, Craft, and Art Architecture.” I admired Soleri’s work, several bridge designs, as well as a desert house with a retractable dome roof. A few years later, I almost made it to Arizona but an opportunity to do graduate work intervened. At that time, Soleri (born in Italy, apprenticed with Wright) was already a mythical if somewhat elusive figure. In 1978, Stewart Brand invited me to the Whole Earth Jamboree; the deal was that you could speak to the assembled crowd (8,000 people) on any subject at all—but only for five minutes. Irresistible. The jamboree took place on a rifle range in a military reservation on the Marin headland, and accommodations were army pup tents. My wife and I struggled to put up the tent, and like most people made a botch of it. I looked over to the next tent and recognized Soleri; his tent was perfectly pitched, taut as a sheet of plywood. I can’t recall what he spoke about (I do remember Peter Coyote’s talk), most of the day was spent waiting for Marlon Brando—who never showed up. By then, Soleri had shifted to his guru mode. I was never much convinced by his “city,” Arcosanti, neither architecturally, nor urbanistically. It seemed a hand-crafted version of the misguided megastructure ideas of the time. But I still wish I had gone to the desert and learned how to cast bells.

THE LATEST

Coming October 8