BACK TO THE FUTURE

A friend asked me what I thought of the design of the recently unveiled Tesla Cybercab. The BBC website called the car “futuristic-looking,” perhaps because it has a sleek body and gull-wing doors. The latter are better described as “backward-looking,” since they were first introduced by Mercedes-Benz 70 years ago, and had a brief—very brief—revival in the 1981 De Lorean. I haven’t seen a Cybercab, only photographs, but the question made me think of EV car design in general. It strikes me that the “problems” that EV design is solving often remain murky. The unpleasantly delicate door handles of Teslas, for example. Reducing drag resistance used to be a major issue in car design, but efficient electric motors deliver so much torque in terms of acceleration and top speed, compared to an internal combustion engine, that the streamlined appearance of most EVs doesn’t make much sense. I suspect that EV design is driven more by marketing than by performance. Getting rid of dials and controls, and putting all the controls on one touch-screen, looks neat but what exactly does it solve. In my 1993 Benz I could control heat, lights, radio etc, by flicking a switch without taking my eyes off the road.

A WRITING LIFE: PART THREE

In 2004 I got a call from Jacob Weisberg, the editor of Slate. Would I be its architecture critic? Sixteen years earlier I had written a column for Wigwag, a short-lived general interest magazine that had been done in by the 1991 recession. But I was now 61, which seemed a bit old for an online magazine that appeared to be staffed by twenty somethings. I told Jacob that if I accepted I was not interested in simply reviewing new buildings. He said that was fine with him. Over the next six years I wrote 133 essays and slide shows. “Supersize My House,” “Don’t Count Your Titanium Eggs Before They’re Hatched,” and my favorite, “Tall Buildings, Short Architects.”

A WRITING LIFE: PART TWO

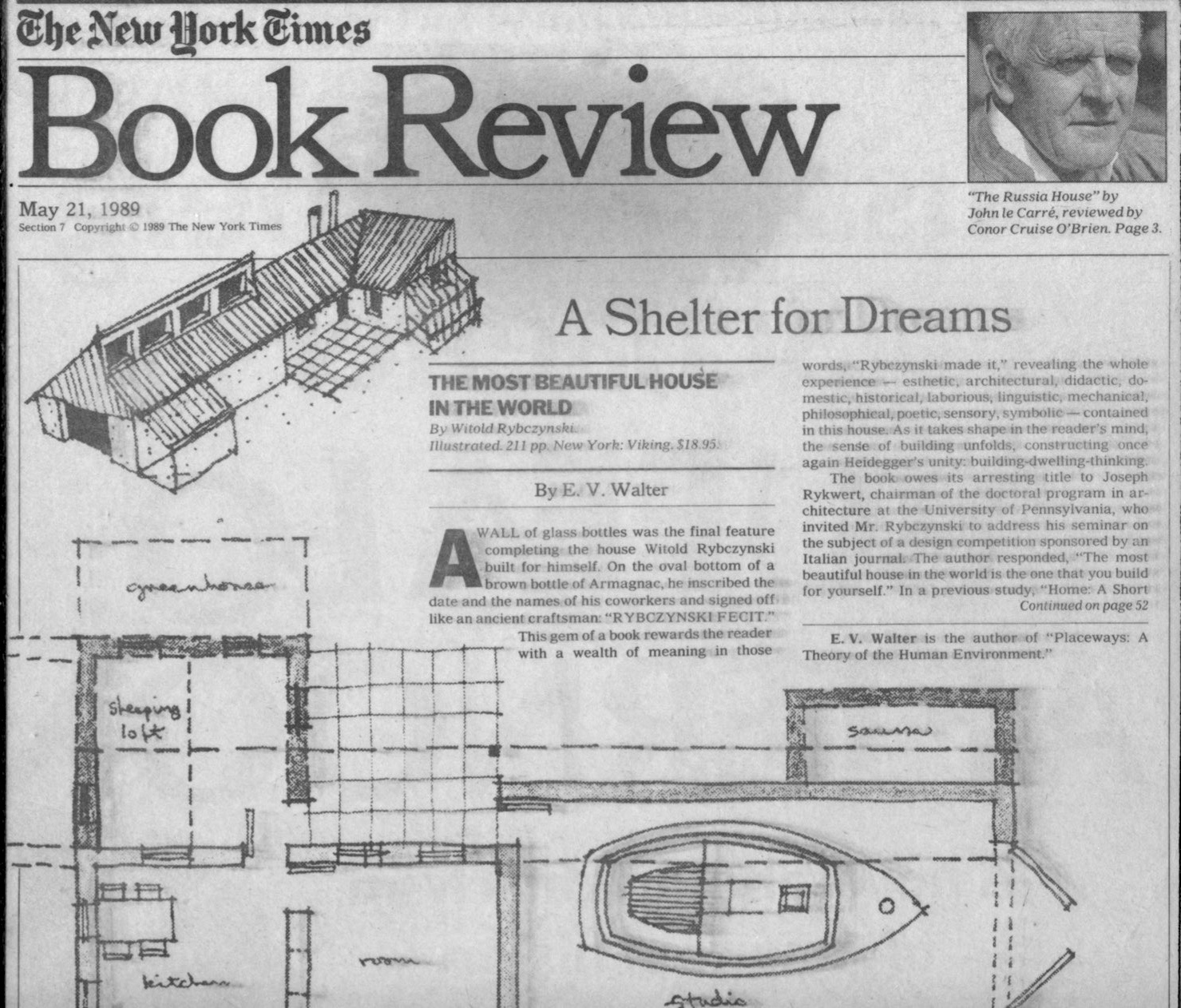

In 1989, three books later, I wrote The Most Beautiful House in the World, about how my wife Shirley and I built our own house in rural Quebec. The book was reviewed on the front page of the New York Times Book Review, and made it to the bestseller list. Later that year I got a call from a Times editor who invited me to write something on architecture for the Arts & Leisure section of the Sunday paper. I was taken aback because although I was an architect, I had written articles and book reviews on other subjects, but I had never been asked my opinion about architecture. I realized that in America (I was still living in Canada at the time) my successful book meant I was now an expert. I wrote “Architects Must Listen to the Melody.” It began, “Goethe once described architecture as frozen music; if he was right, could cities be described as congealed concertos?”

A WRITING LIFE: PART ONE

In the 1970s I belonged to the Minimum Cost Housing Group at McGill University in Montreal. Our research included third world slums, alternative technology, composting toilets, well, that was the seventies. We published and sold booklets—Stop the Five Gallon Flush was the most successful. Around 1978 I thought it would be a good idea to combine all the publications in a book—after all, this was the era of the Whole Earth Catalog and the Domebook. I didn’t have much success finding a trade publisher. I did get one positive response from Bill Strachan, a Doubleday editor. He was not keen about my proposal, but he had read a short article of mine in Stewart Brand’s little magazine, CoEvolution Quarterly. Would I consider expanding my article into a book, he asked? Why not, I thought. Paper Heroes: A Review of Appropriate Technology was my first book. (The jacket above is from the 1991 Penguin edition.)

OPEN BUILDING

My friend Steve Kendall gave me a copy of his latest book, written with the late John Habraken, Open Building for Architects. Wiki defines Open Building as “an approach to the design of buildings that takes account of the possible need to change or adapt the building during its lifetime.” Reflecting on this ambitious goal—buildings can last for centuries—led me to a conclusion: There’s no such thing as Open Building. Or, to put it another way, buildings have always been open to change.

I am put in mind of the Uffizi Museum (originally magistrates’ offices), the Louvre, the Hermitage, the Belvedere (originally royal and imperial palaces), the Tate Modern (originally a power station), the Musée d’Orsay (originally a railway terminal), the National Portrait Gallery (originally the Patent Office), and the Prado (originally designed as a science museum). Of course, these are all famous museums, but Europe is full of palazzos, mansions, and hôtels, that have found second and third lives in a variety of altered uses.

Closer to home, consider building change in my city, Philadelphia. Innumerable row houses have been converted to non-residential uses, innumerable industrial lofts repurposed to residential use,

GOD-KNOWS-WHAT-KIND-OF-CLASSIC

I read Catesby Leigh’s interesting article, “Uncle Sam’s Buildings,” in The American Conservative. He argues in favor of the federal buildings that were built in the prewar era, and which more or less followed the classical style, and is critical of the modernist era, perhaps best characterized by the awful FBI headquarters building in DC. His essay brought up a question for me. The examples of classical federal buildings that he admires are all from a particular era, and his essay implies that this architectural style should continue ad infinitum. Whatever the merits of this suggestion, it does fly in the face of all we know about history. Architecture has never stood still: Bramante was followed by Bernini, then Wren, then Edwin Lutyens, then Paul Cret. There are many examples of federal buildings of the 1930s (which Leigh conveniently ignores), that represent a different sort of traditional approach: in my city, Philadelphia, Rankin & Kellog’s main post office across from 30th Street Station (illustrated above), and Harry Sternfield’s Nix federal courthouse and post office; in DC, Cret’s Federal Reserve Board Building, and Bertram Goodhue’s National Academy of Sciences on the National Mall. None of these architects used the usual paraphernalia of Beaux-Arts classicism,