CHRISTOPHER ALEXANDER (1936-2022)

When I was a student at McGill, my friend Ralph Bergman and I started a magazine, Asterisk, actually it was named *. The second issue, this was 1964, included an article by Alexander and the architect B.V. Doshi on designing a village in India. A couple of years later, when I was working on my thesis, another classmate, Richard Rabnett, had come across HIDECS, Alexander’s computer program for ordering criteria in architectural design. It was in FORTRAN, and we laboriously entered our information onto punch cards, although we never could get the program to run (years later I learned that HIDECS was flawed and could not actually run). My next encounter with Alexander was in 1978 in Mexico City. I had been invited to speak at a symposium at the Universidad Nacional—Alexander would deliver the keynote. Expecting the usual sparse turnout I was amazed to find an audience of several hundred excited students—not there for me, I hasten to add. The previous year, Alexander had published A Pattern Language, and it had turned him into an international star. I had a copy, of course. One of his principles was that design could not be disconnected from the actual process of construction.

A HOLIDAY FROM HISTORY

I was listening to a conversation between Peter Robinson and Bari Weiss on the Hoover Institution’s Uncommon Knowledge podcast. I was brought up short by Weiss’s phrase: “a holiday from history.” Weiss and Robinson were talking about what she called The Great Unraveling, but it struck me that a “holiday from history” could easily refer to architecture, which since roughly the 1920s has turned away from the past. Where once architects had learned their art in part by studying history, whether in books or through travel, they now had their vision resolutely focused in only one direction—the future. In that way, design was simplified. No need to take on Mr. Bramante or Mr. Wren (to use a Hemingwayesque locution)—you were free to make your own rules. This was at first exciting, and one sees this excitement in the early work of Corbusier and Mendelsohn. But succeeding generations have found the holiday from history could also be a bit of a bore, as well as a challenge—it is not so easy to continually reinvent an architecture “for our time.” All holidays come to an end, of course. Will architects return to a more tried and true method: looking back in order to move forward,

NOT QUITE ALONE

It is a curious thing, this new solitude of mine. More than one person has told me “You will always have the memories of your life together.” Well, I suppose that’s true, but life exists in the present, not the past, and it is in my daily routines that Shirley is most present. After almost five decades, many of my habits are entwined with hers: how I cook, or shop, or simply look at the world. There is a downside: many of the things we did together—eating out, traveling, going to a museum or a concert, watching Jeopardy—have lost their appeal. These things only remind me that she is no longer able to enjoy them. But every time I do the laundry I remember her instructions; take care of this, make sure of that. I am alone, and yet not quite.

Photo:Castellana Hilton, Madrid, April 1976

THE ONE THAT GOT AWAY

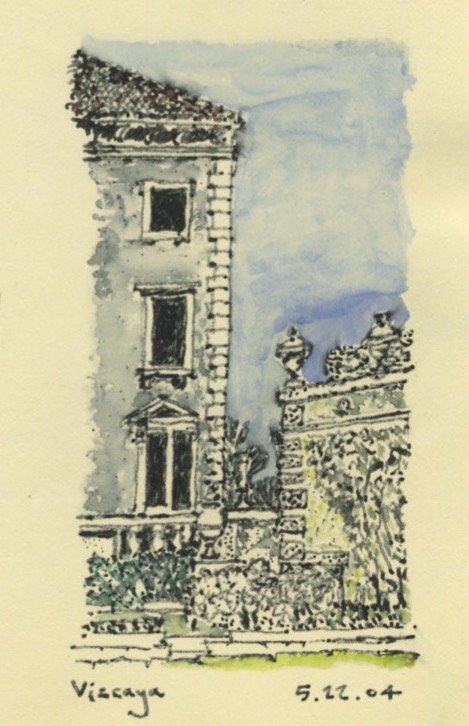

Robert A. M. Stern has just published Between Memory and Invention: My Journey in Architecture. This is not a review; I’ve only read the first chapter—on Amazon—which details the author’s childhood. But Stern’s book is not exactly an autobiography; the publisher calls it “a personal and candid assessment of contemporary architecture and his fifty years of practice.” In fact, architectural memoirs are few and far between. With the exception of Frank Lloyd Wright’s famously unreliable An Autobiography, I only know of two modern examples, Nathaniel Owings’s The Spaces in Between: An Architect’s Journey (1973), and A. Eugene Kohn’s The World by Design: The Story of a Global Architecture Firm (2019). I think there are a number of explanations. Writers keep journals; architects carry sketchbooks—theirs is a visual not a literary imagination. More to the point, architecture is a profession, which makes candid recollections tricky, like telling tales out of school. I once asked Gene Kohn about a recent KPF project that seemed to me awkward. “Yes,” he answered. “That one got away from us.” We were, of course, speaking privately. Difficult clients, design mistakes, and missed opportunities are a part of every architect’s “journey,” but they are always discreetly kept out of the public eye.

NOT INTERESTED

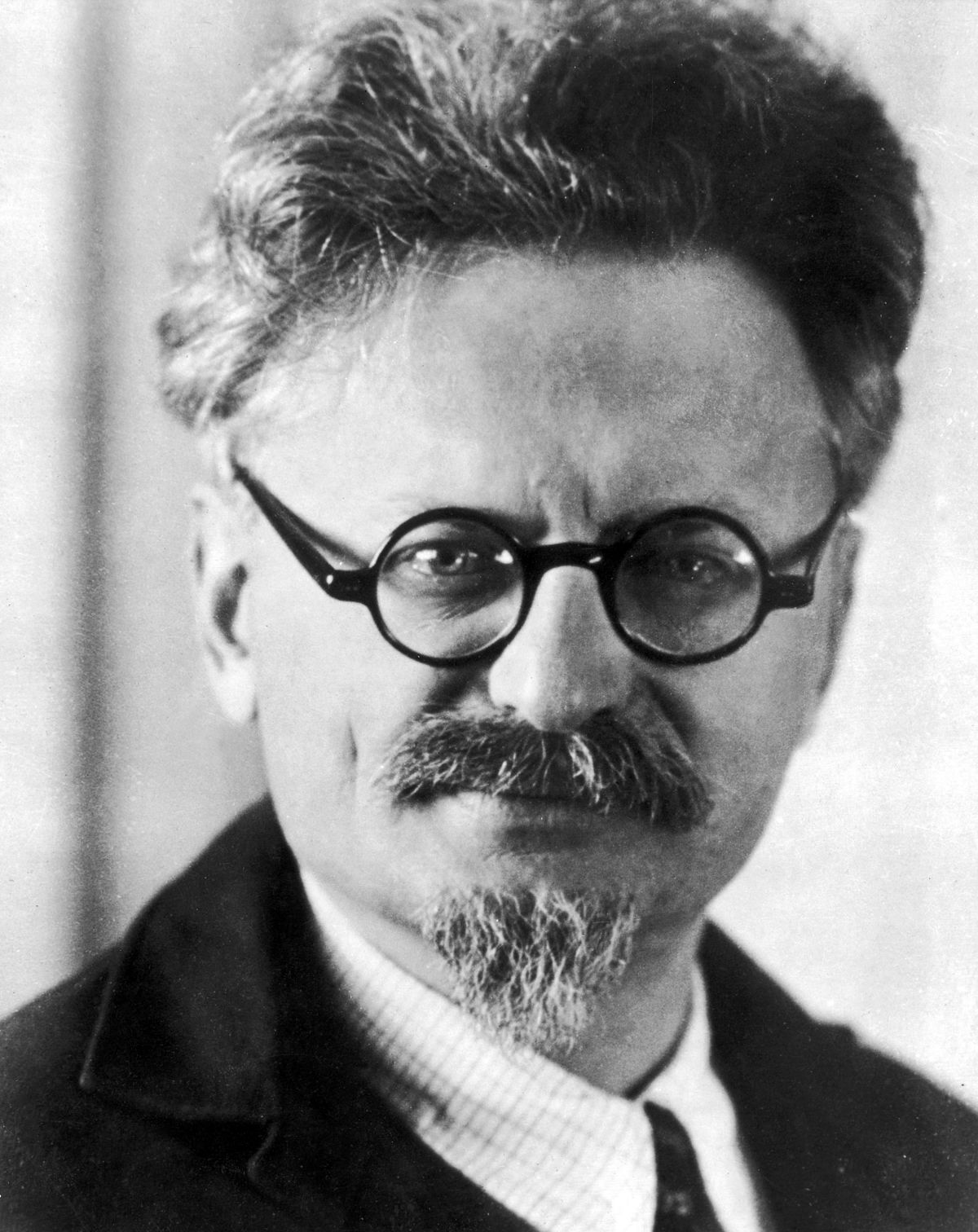

In this difficult time the famous Leon Trotsky quote comes to mind: “You may not be interested in war, but war is interested in you.”

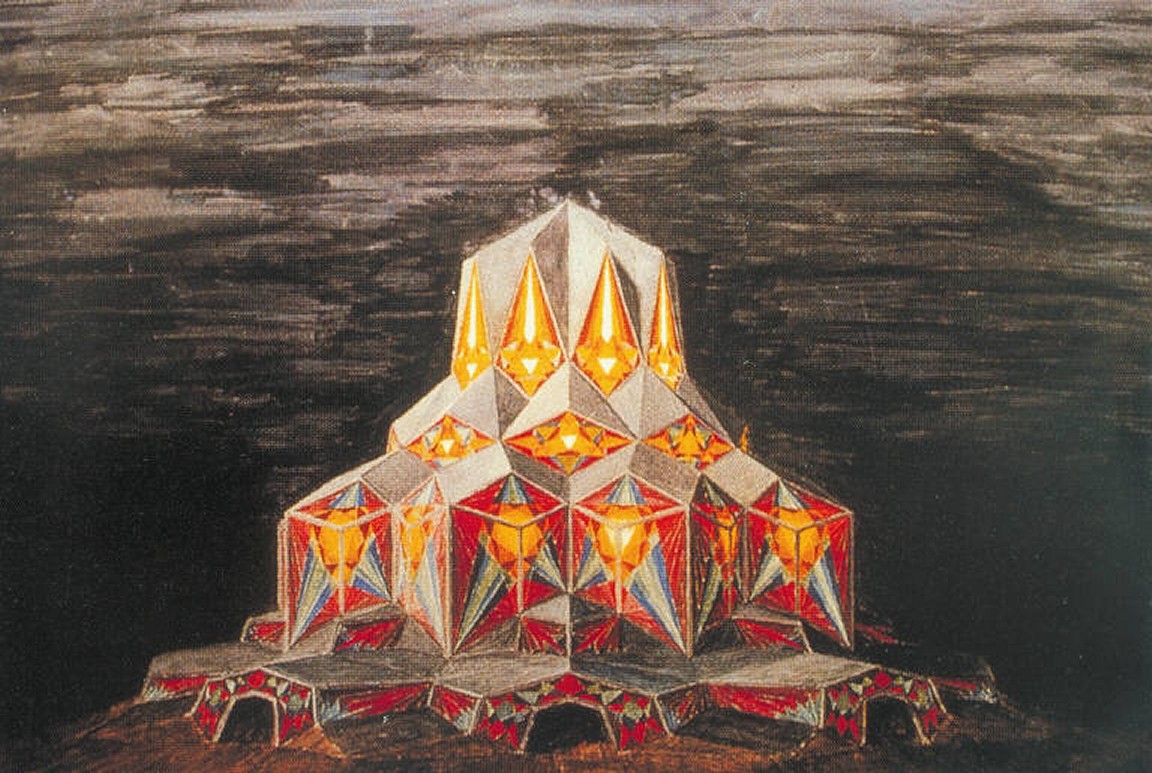

CRYSTAL CITY

Paul Scheerbart (1863-1915) was a German writer of the turn of the nineteenth century; today we would call him a sci-fi author. In 1914 he wrote a novel with the unwieldily title The Grey Cloth and Ten Percent of White. The protagonist is an architect, more specifically a “glass architect,” and Scheerbart dedicated the book to Bruno Taut, a Berlin architect who promoted the idea of revolutionary all-glass buildings. Glasarchitektur (the title of another Scheerbart book) was an avant-garde obsession; Taut imagined “glowing crystal houses and floating, ever-changing glass ornaments.” When I look out my window I can see his crystal city come to life. It is certainly glowing, especially on a sunny day. Ever-changing? Well sort of. What is missing is the color and jewel-like qualities of Taut’s rather beautiful sketches. And the mute glass boxes undermine traditional architectural qualities such as mass and shadow, structure and weight, but I suppose that was the whole point of glasarchitektur.

Image: “The City Crown,” Bruno Taut, 1919.