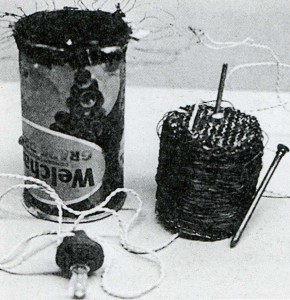

“I really do believe that the world can be saved through design, and everything needs to actually be ‘architected,’ ” Kanye West recently told Harvard students in a widely-repeated quote. Architects especially loved it, but Lucas Verweij, a Berlin-based writer, argues in Dezeen that claims such as West’s are excessive. Verweij writes that the expectations placed on design—“design can solve the smog problem in Beijing, the landmine problems in Afghanistan and huge social problems in poor parts of Western cities”—are overblown and cannot be met. “We are in a design bubble,” he writes, “it’s a matter of time before it will burst.” I’m not sure about the bubble—it seems more like a passing fashion to me—but the current idea that every problem is fodder for the design profession is certainly misguided. Can a designer really be master of all trades? The proposition that design can be effective at all scales dates back to Walter Gropius, who claimed that the designer could assume broad responsibilities, from a teacup to a city was how he put it. (Grope’s teacups are OK, his urbanism, not so much.) But design is primarily about the how; the what is determined by a host of circumstantial conditions—social, economic, and cultural—over which the designer exercises no authority. More than 40 years ago, Victor Papanek, a Viennese-born industrial designer, wrote Design for the Real World, in which he made the case for design-as-problem-solving as opposed to design-as-styling. It was compelling stuff—I remember a Third World transistor radio housed in a can, run by candle-power. But were such radios ever produced? The forces of globalism ensured that it was the cell phone, not the the tin-can radio, that revolutionised the world, including the Third World. And the revolutionary aspects of the cell phone are the work of engineers, not industrial designers. The much-vaunted “design” of Apple products, for example, is chiefly (obsessively) minimalist packaging. Pace Papanek.