Revivalism in architecture refers to a style that consciously echoes or evokes the style of a previous era. This blurs an important distinction. The Italian Renaissance and the British Gothic Revival were echoing the styles of earlier eras, earlier local eras. The Greek Revival, on the other hand, whether it occurred in Berlin, Edinburgh, or Philadelphia, was a foreign style from far away; it was a transplant. That did not mean that it was less authentic, but it did give it a different meaning. When Robert A. M. Stern built Franklin and Murray colleges at Yale in 2017, he was reviving James Gamble Rogers’s Collegiate Gothic of the previous century. But Rogers had not revived a local tradition; his inspiration was a collection of postcards and photographs of Oxbridge colleges (that he had not visited). He was transplanting.

READ ALL ABOUT IT

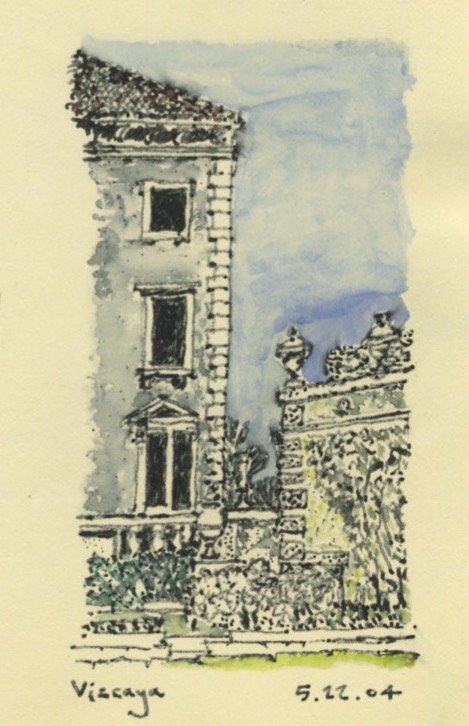

I came across this confident statement in the September issue of New York Review of Architecture, in a rather breathless review of a recent book about Aline and Eero Saarinen: “It is through media, of course, that we primarily consume architecture.” I was brought up short. How preposterous, I said to myself. But on second thought I realized that it was all too true. If there is an audience for architecture—and judging from the almost total absence of architecture columns in the mainstream press one has to be doubtful—it’s likely that its chief connection with architecture is through media rather than first-hand experience.