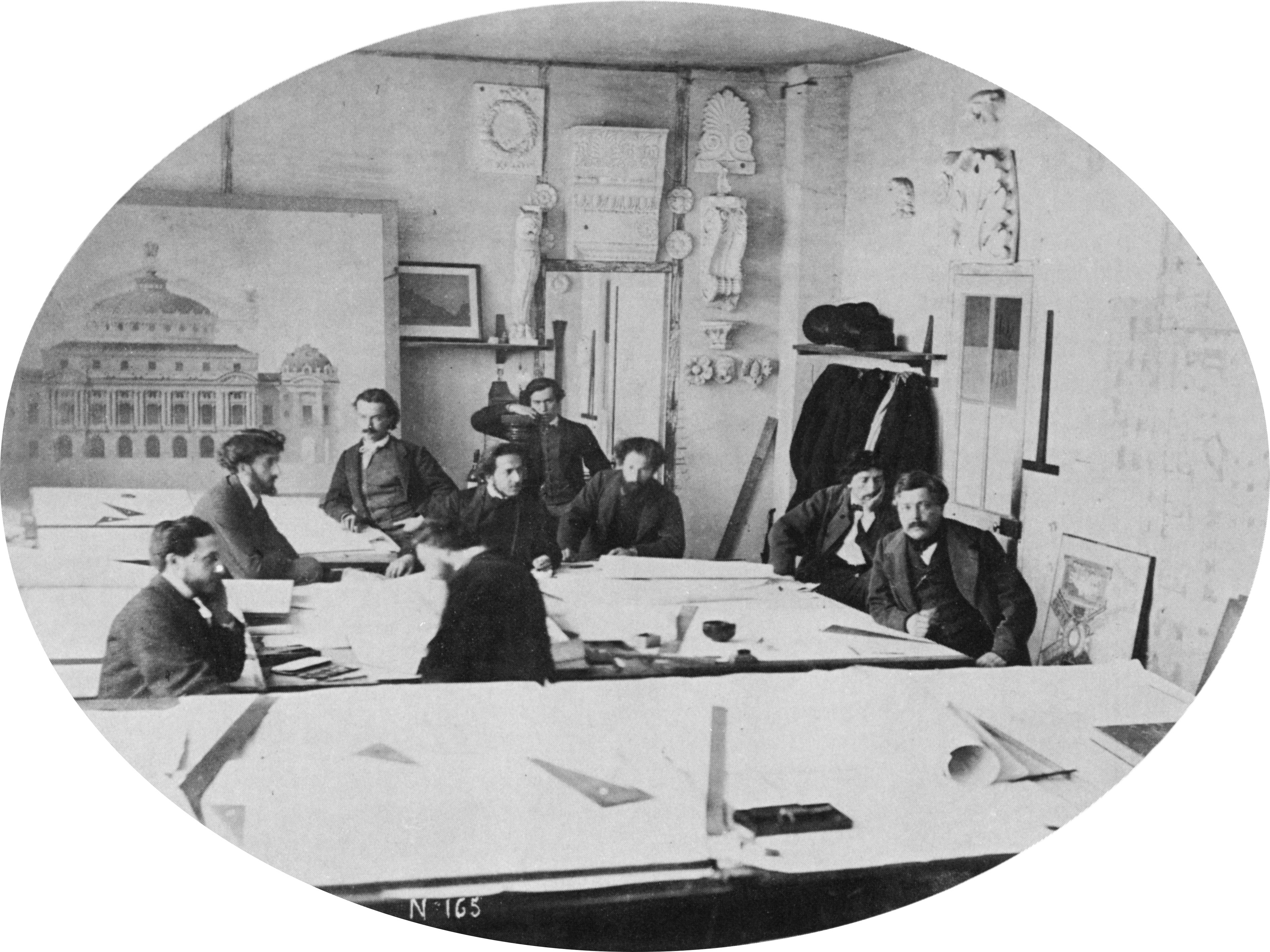

THE TALENTED MR. CRET

Perhaps the most televised twentieth-century work of American architecture is the Federal Reserve headquarters (Eccles Building) in Washington, D.C., designed by Paul Philippe Cret (1876-1945) in 1938. Cret’s stripped classical facade inevitably accompanies any report on the Fed on the nightly news. Now Cret has a twofer: Walter Reed National Military Medical Center in Bethesda, where President Trump was taken for treatment of Covid-19. Walter Reed was designed by Cret in 1939-42. It is said that President Roosevelt suggested the twenty-story tower to Cret after visiting Bertram Grosvenor Goodhue’s Nebraska State Capitol. Walter Reed is an example of Cret’s late style,