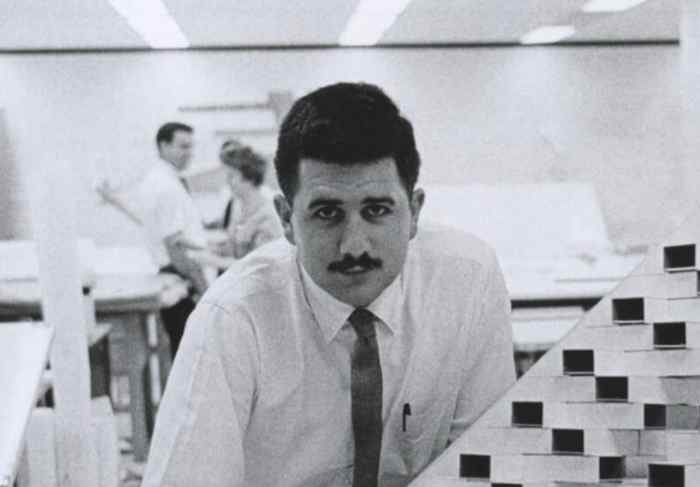

JACK DIAMOND

The architect Jack Diamond (1932-2022) died last week. He was perhaps Canada’s leading architect. Yet no-one would refer to him as a starchitect. “It’s easy to do an iconic building,” he once said, “because it’s only solving one issue.” Diamond’s designs were never one-dimensional. His opera house in Toronto is a traditional horseshoe-shaped auditorium situated within an unprepossessing blue-black brick box whose chief feature is a glazed lobby facing one of the city’s main streets; dramatic, but hardly iconic—very Canadian. At $150 million in 2008, the cost of the Four Seasons Centre was modest as opera houses go, but more important was how the money was spent—on the hall and the interiors rather than on exterior architectural effects.