The on-going public debate about starchitects, in part prompted by my piece in the New York Times, was not elevated by James Russell’s judgement that the debate was “stupid.” Another common reaction was to affirm that the term itself is meaningless—if not actually a put-down. There have always been architectural stars, the argument goes, Palladio, or Bernini, or whoever. It is true that there have always been well-known architects, even celebrity architects, but the starchitect phenomenon is different. The term is an accurate description of a certain (small) category of practitioners today. Moreover, today’s stardom is not analogous to architectural fame in the past. In his interesting new book, The Globalisation of Modern Architecture, the British architect Robert Adam quotes David Chipperfield: “It’s easier to know about architects than architecture. A banker won’t know about architecture but will know that ‘Zaha Hadid’ or ‘Rem Koolhaas’ is a brand.” Moreover, the brand has quantifiable monetary value since it can be measured in terms of increased fund-raising, greater museum attendance, higher office rents or condo selling prices, or patron satisfaction in the case of campus buildings. In that sense, the starchitect is equivalent to the Hollywood star, an actor whose name on a film proposal makes it bankable. The analogy with Hollywood is useful: not all the best actors are stars, and the stars are not necessarily the best actors. It is not a measure of quality but of name recognition among the moviegoing pubic. So, too, in architecture; starchitects are not necessarily the “best” architects. “To be a starchitect, whether voluntarily or otherwise,” Adam writes, “is to be a global brand, and star architects are chosen to give their brand value to projects.”

The on-going public debate about starchitects, in part prompted by my piece in the New York Times, was not elevated by James Russell’s judgement that the debate was “stupid.” Another common reaction was to affirm that the term itself is meaningless—if not actually a put-down. There have always been architectural stars, the argument goes, Palladio, or Bernini, or whoever. It is true that there have always been well-known architects, even celebrity architects, but the starchitect phenomenon is different. The term is an accurate description of a certain (small) category of practitioners today. Moreover, today’s stardom is not analogous to architectural fame in the past. In his interesting new book, The Globalisation of Modern Architecture, the British architect Robert Adam quotes David Chipperfield: “It’s easier to know about architects than architecture. A banker won’t know about architecture but will know that ‘Zaha Hadid’ or ‘Rem Koolhaas’ is a brand.” Moreover, the brand has quantifiable monetary value since it can be measured in terms of increased fund-raising, greater museum attendance, higher office rents or condo selling prices, or patron satisfaction in the case of campus buildings. In that sense, the starchitect is equivalent to the Hollywood star, an actor whose name on a film proposal makes it bankable. The analogy with Hollywood is useful: not all the best actors are stars, and the stars are not necessarily the best actors. It is not a measure of quality but of name recognition among the moviegoing pubic. So, too, in architecture; starchitects are not necessarily the “best” architects. “To be a starchitect, whether voluntarily or otherwise,” Adam writes, “is to be a global brand, and star architects are chosen to give their brand value to projects.”

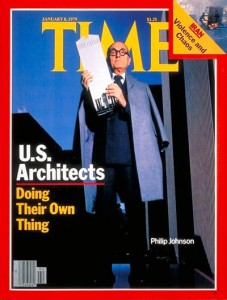

Who was the first brand-name architect? It would surely have been Jørn Utzon, had he not resigned before the Sydney Opera House opened in 1973. My own choice would be Philip Johnson, who graced the cover of TIME magazine (January 8, 1979) with a model of the AT&T building. Most businessmen didn’t know what Johnson stood for (if he stood for anything), but they recognized the name—enough to add value to Gerald Hines’s Johnson-designed real estate development projects. Johnson was a national star. It would not be until 1997 and the opening of the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao that a starchitect became a global brand.