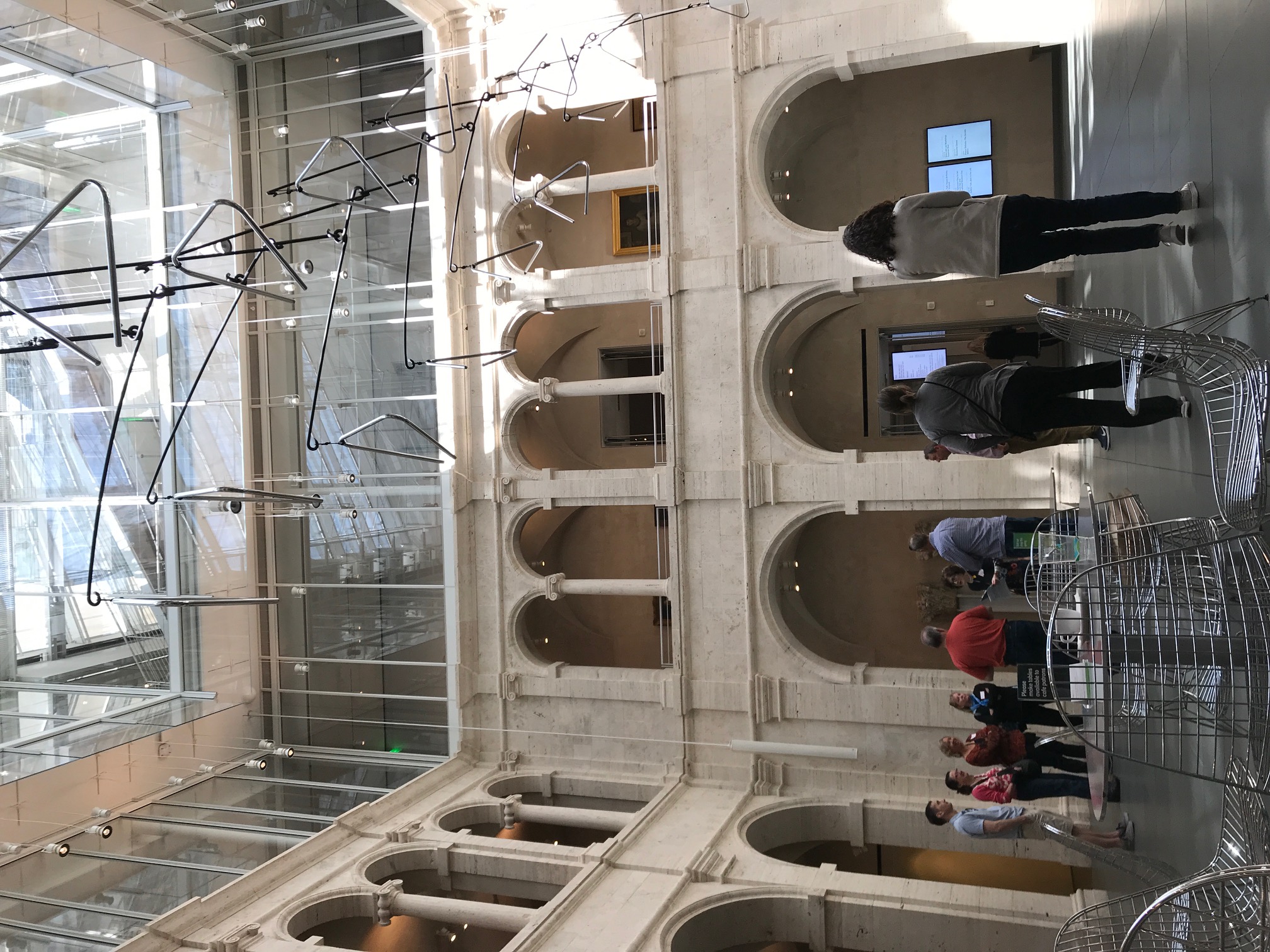

Harvard’s Fogg Museum, a Colonial Revival building at 32 Quincy Street, reopened five years ago after Renzo Piano’s major expansion, or “reboot” as The Guardian called it. The other day I had a free hour and I spent it in the Calderwood Courtyard of the old/new building. The architect of the original museum, Charles Coolidge of Coolidge, Shepley, Bulfinch and Abbot (H.H. Richardson’s successor firm), modeled the cloister-like arcades on the loggia of a sixteenth-century canon’s house in Montepulciano, designed by Antonio da Sangallo the Elder. Admittedly, the modeling is very loose, more like a stylized memory, and has a kind of American crispness in execution that is very different from the original. Piano added two stories on top of the arcade making a sort of spumoni—modern above, Renaissance below. The modernist layer is thin fare; Piano’s work, with its fussy greenhouse roof, looks provisional, like a temporary addition. I came to the conclusion that there were three chief reasons. 1) Steel and glass are simply not as engaging as travertine. 2) The orders of the arcades play with scale; the anonymous minimalist addition is more like utilitarian engineering—nothing but the facts ma’am. 3) The modeled arcades are defined by sharp shadows; Piano’s addition, which is mostly glass, contains no shadows. If architecture is indeed the “the masterly, correct and magnificent play of volumes brought together in light,” then the addition is not architecture at all. In the old arcades, our glance is caught by the details of the Ionic and Doric capitals; in the new addition there are no details (except for the lighting fixtures), and we quickly loose interest. Almost 400 years separate Coolidge’s work from that of Sangallo; less than 90 years later, Piano comes along and and it’s all gone.

This essay demonstrates why like to read articles by people who are smarter than I am. The three insights are natural and logical once read, but had never entered my mind when I looked at the revamped museum.

No believer, I, in the Modernist ‘Preservation’ dogma — a spinoff of the dreadful ‘zeitgeist theory’– that would dictate reprising or matching existing ‘historical styles’ in alterations /additions to existing buildings out of the question.

However, although skeptical about what Piano might have done to the old Georgian Revival Fogg — his work tends toward a bland, generic sameness– I was pleasantly surprised on my recent return to Cambridge to see what felt like a very successful work. The addition exhibits a light touch that belies the outsize added volume and program to the existing. It feels light and ‘airy’ and beautifully deferential to the superbly elegant and well crafted existing Courtyard that remains the building’s singularly memorable interior feature. This in fact renders the existing Courtyard almost itself a highlighted central ‘object on exhibit’.

The building has been rendered roomy, light-filled and fully functional and responsive to its evolved complex program.

Beyond this, urbanistically, the addition is brilliant in how it reconciles with its cheek-by-jowl-adjacent neighbor, LeC’s

Carpenter Center. It links very plausibly and functionally to the previously ‘vestigial’ / ‘stranded’ Prescott St. end of that building’s traversing ramp. No mere empty ‘formalist’ gesture in this but an enlivening link to the Fogg’s new added entry on Prescott as well as a strong link right down to well-pedestrian- traffiqued B’way.

As stated, no huge fan of Piano’s work, generally speaking, but ,here, a job very well done.