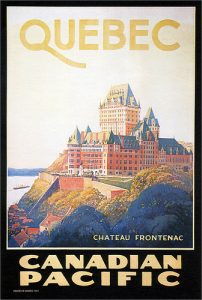

The Canadian design mag, Azure, ran a post recently titled “Canada 150: Canada’s Future Role in Architecture and Design.” The magazine posed the question to a number of prominent and not-so-prominent architects. Predictably, perhaps, the answers were uniformly upbeat: a world leader in sustainable design, a catalyst for change, and my favorite, in the forefront of developing pluralistic cultural identity. Perhaps it’s worth looking back to get an idea of the future. International leadership doesn’t loom large. The list of Canadian architects whose names would appear in an encyclopedia of world architecture covering 1867-2017 would not be long. There was no H. H. Richardson to shake up the architectural scene, no Charles McKim to establish a classical standard for civic buildings, no Frank Lloyd Wright to preach a northern organic gospel. Modernism, when it arrived, tended to be a pale imitation of what was going on south of the border. It is not until Arthur Erickson that we find a native-born Canadian architect who develops an original style that has an impact on the international scene. He is followed by Moshe Safdie and John Andrews, immigrants both, who make their mark with Habitat and Scarborough College. I would add two stylistic outliers, whose idiosyncratic approach ruled them out of fashion but who deserve at least a footnote: Montreal’s Ernest Cormier and Ron Thom. The latter’s Massey College is an original masterwork that demonstrates how Wrightian ideas might be adapted north of the 49th parallel. Erickson might have become Canada’s Aalto, had his architecture been a little less theatrical, a little more, well, Canadian. The frosty Canadian climate and long winters don’t demand—or tolerate—flamboyance or whimsy. They do demand robust construction; zoomy shapes covered in Dryvit just don’t cut it. In any case, Canadians were never much interested in iconic buildings. There is no neoclassical Macdonald Memorial or Parliamentary Dome. Perhaps the closest you get to a national icon, apart from the Peace Tower, is the series of romantic chateau-like CPR hotels built at the end of the nineteenth century—and they were designed by Bruce Price, an American,

The Canadian design mag, Azure, ran a post recently titled “Canada 150: Canada’s Future Role in Architecture and Design.” The magazine posed the question to a number of prominent and not-so-prominent architects. Predictably, perhaps, the answers were uniformly upbeat: a world leader in sustainable design, a catalyst for change, and my favorite, in the forefront of developing pluralistic cultural identity. Perhaps it’s worth looking back to get an idea of the future. International leadership doesn’t loom large. The list of Canadian architects whose names would appear in an encyclopedia of world architecture covering 1867-2017 would not be long. There was no H. H. Richardson to shake up the architectural scene, no Charles McKim to establish a classical standard for civic buildings, no Frank Lloyd Wright to preach a northern organic gospel. Modernism, when it arrived, tended to be a pale imitation of what was going on south of the border. It is not until Arthur Erickson that we find a native-born Canadian architect who develops an original style that has an impact on the international scene. He is followed by Moshe Safdie and John Andrews, immigrants both, who make their mark with Habitat and Scarborough College. I would add two stylistic outliers, whose idiosyncratic approach ruled them out of fashion but who deserve at least a footnote: Montreal’s Ernest Cormier and Ron Thom. The latter’s Massey College is an original masterwork that demonstrates how Wrightian ideas might be adapted north of the 49th parallel. Erickson might have become Canada’s Aalto, had his architecture been a little less theatrical, a little more, well, Canadian. The frosty Canadian climate and long winters don’t demand—or tolerate—flamboyance or whimsy. They do demand robust construction; zoomy shapes covered in Dryvit just don’t cut it. In any case, Canadians were never much interested in iconic buildings. There is no neoclassical Macdonald Memorial or Parliamentary Dome. Perhaps the closest you get to a national icon, apart from the Peace Tower, is the series of romantic chateau-like CPR hotels built at the end of the nineteenth century—and they were designed by Bruce Price, an American,

On Culture and Architecture

Seems to me that Douglas Cardinal ‘s work is worthy of mention, being native-born.

Personally I find a little of Cardinal’s warmed-over Mendelsohnian expressionism goes a long way, but perhaps that’s a matter of taste.

How about native Canadian architect Douglas Cardinal? He’s left quite a legacy of important buildings.

I agree. Douglas Cardinal’s work is unique, tied to the landscape and to the native peoples.