CHARM AND GRANITE

I was saddened to learn of the death of David Childs (1941-2025). He was the chair when I joined the Commission of Fine Arts, and an intelligent architect and a charming man. Reading the obituaries put me in mind of something I came across while writing The Biography of a Building, about the Sainsbury Centre for the Visual Arts, a very early Norman Foster design. Sir Hugh Casson, the dean of postwar British architects, had written a letter of recommendation for the young Foster, who was being considered for the job: “As you have already met him [Foster], you need not be told that he is a man of great energy, drive and enthusiasm, with enough granite beneath the charm to ensure consistency in any project to which he lays his hand.” Charm is a professional requirement for an architect; granite is a rarer attribute.

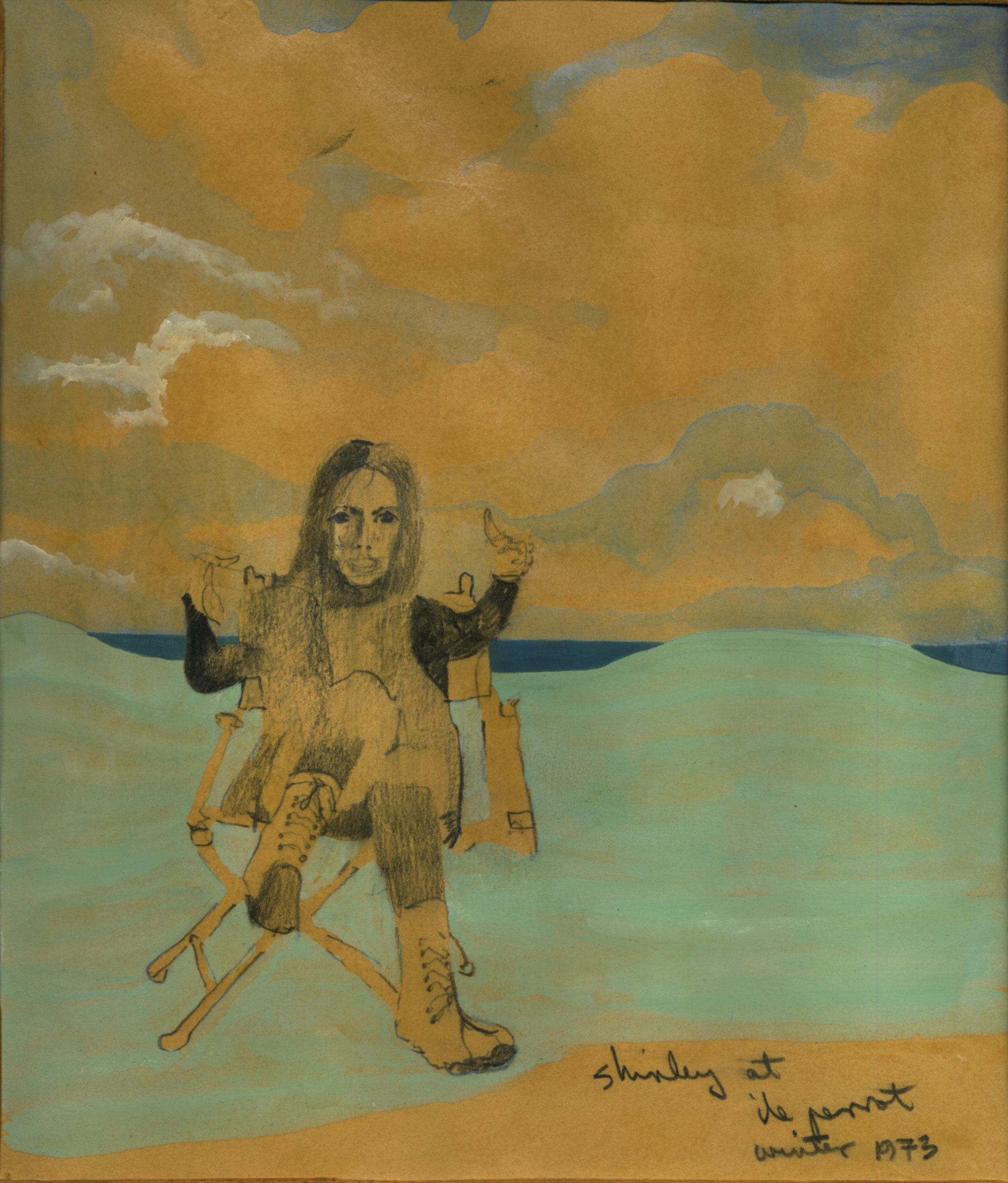

MAKE ME AN ANGEL

I’ve been re-watching that excellent TV series, Ozark. The last episode included one of the characters—actually his ghost, there’s a lot of dead people in Ozark—singing a song whose melody was familiar although I couldn’t place it immediately. It was John Prine’s “Angel from Montgomery.” The mournful music evoked my Shirley, who loved Prine. I think it was his ironic lack of sentimentality that appealed to her. She also liked Joe Cocker, Randy Newman, Blossom Dearie, anything by Cole Porter. And Janis, whom she heard at Woodstock.

FUSION ON THE MAIN LINE

The other day I had the opportunity to visit Camp-Woods, a house on Philadelphia’s Main Line. It was built in 1910-12 for James M. Willcox, a banker who would later be president of the Philadelphia Saving Fund Society—and would commission the PSFS Building, America’s first International Style skyscraper. Camp-Woods is definitely not International Style, according to the brief Wiki entry it is Italianate-Georgian. While the architecture is a fusion, that is a misleading description. The architect was Howard Van Doren Shaw (1869-1926), one of the leading residential architects of his day—he was awarded the AIA Gold Medal, a high honor at that time. Shaw was a Chicagoan. After graduating from Yale and MIT he apprenticed with William Le Baron Jenney, the steel-frame pioneer who mentored Louis Sullivan. Like Sullivan, Shaw was neither a revivalist nor a modernist. He belonged to The Eighteen, a luncheon club that brought together architects with an Arts & Crafts sensibility—Frank Lloyd Wright was a member. Shaw and Wright were probably the two leading residential architects in Chicagoland in the early 1900s, but unlike Wright, Shaw worked with a rich palette, which is what informed the design of Camp-Woods, his only East Coast commission.

THE PILLAR BOX

I dislike e-cards for Christmas. They are impersonal and seem to say “we couldn’t be bothered.” I still send cards, sometimes handmade, but there is one part of that that always disappoints: dropping them in the mailbox. The USPS mailbox at the corner is a dismal affair, a cheap, ugly metal receptacle that reminds me of a trash can and always makes me feel as if I’m throwing my letters away. I grew up in England, and I still remember the pillar box, made of sturdy cast-iron, embossed with G VI R and a royal crown, and painted bright red. “Iconic” is a much over-used term, but the British pillar box is exactly that. According to Wiki it dates from 1852, when Anthony Trollope—yes, the novelist—then employed by the Post Office, recommended “letter-receiving pillars” as a way of collecting mail on the Channel Islands. Soon adopted on the mainland, the pillar box has undergone various iterations—there was a hexagonal design, and an unpopular sheet metal version). But it’s the traditional form that has endured: a round, cast-iron column painted red, five feet high, with a domed top, fluted sides, and a base. In other words, a little classical temple.

A HUNGARIAN ARCHITECT IN AMERICA

I watched The Brutalist yesterday. My reaction? An implausible story poorly told and awkwardly stitched together; the Holocaust connection seemed gratuitous; a ham-handedly written script, the audience actually snickered at some of more pompous utterances of the Guy Pearce character; distracting bursts of portentous music at odd moments; and glitches, like Tóth saying square meters when he knows his audience understands only square feet, or producing the kind of expressionistic sketches that are out of character for a Bauhaus-trained architect—more like something the great Eric Mendelsohn would draw. As for the title, while Tóth was definitely brutalized, it made no sense to me, but then not much in this second-rate production did.

My grumpy reaction may have been colored by the greasy smell of my neighbor’s popcorn—a reminded of why I stopped going to the cinema a decade ago.

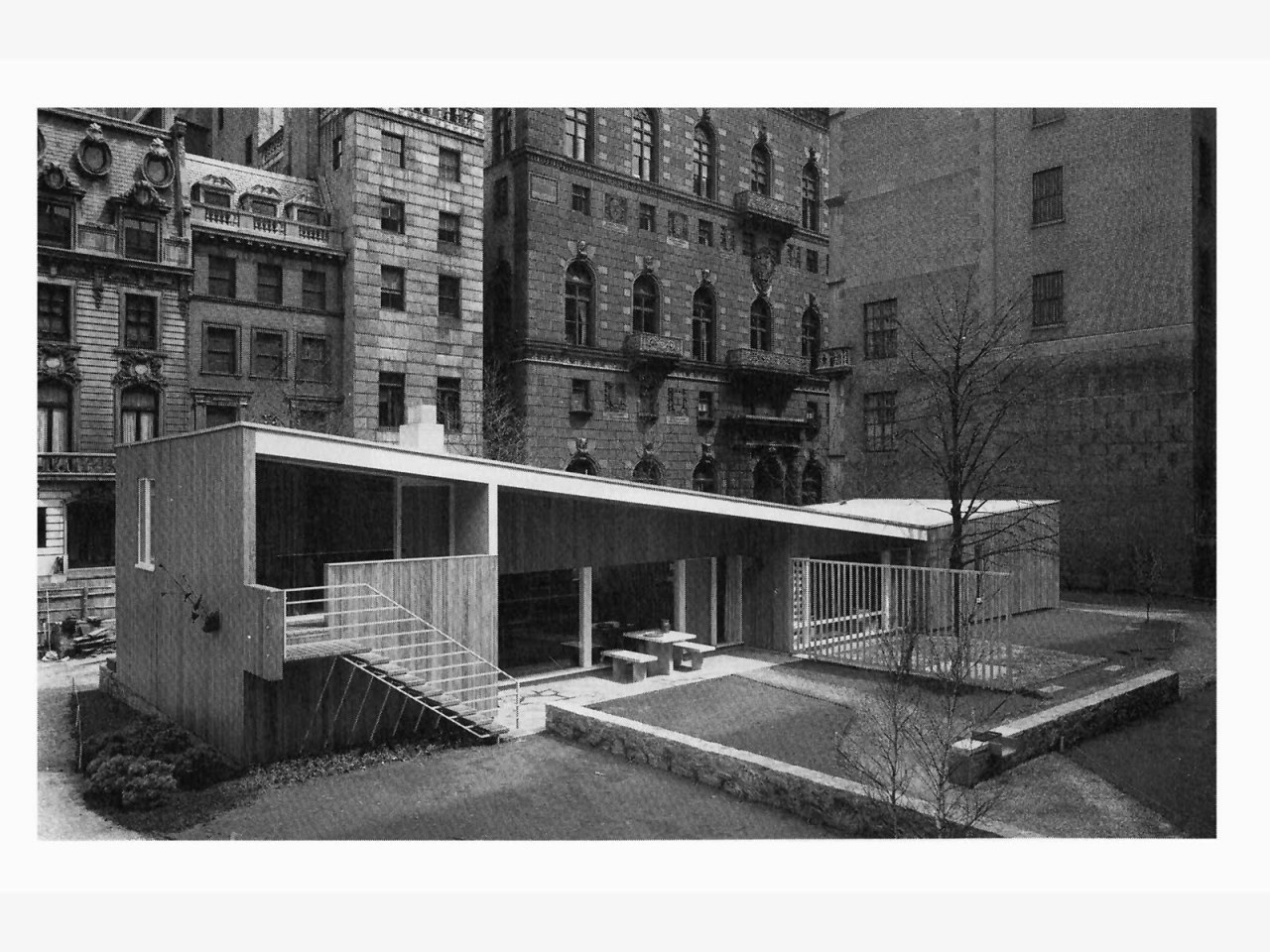

Architecture? The stunning library that Tóth builds for Van Buren does seem like the sort of thing that a talented Bauhausler might design on coming to America, unlike the monumental “community center” that sits uneasily at the center of the film. In 1948 Marcel Breuer, an actual Hungarian immigrant Bauhaus architect, built a modernist house in the MoMA garden (above).

STAINED GLASS

Remember when French premier Emmanuel Macron saw the Notre-Dame fire as an opportunity to modernize the cathedral, and announced an international architectural competition to produce a new, updated roof—a “contemporary gesture,” in his words? And remember when many well-known architects, much to their discredit, applauded the gesture. Macron’s plan was scotched by the almost universal negative reaction of curators, historic preservationists, and the French parliament. Now Macron is back in hot water with his plan to remove six stained glass windows and install modern replacements. The uproar is caused by the fact that the six removed windows were unharmed by the fire, and were in addition the work of Viollet-le-Duc, the architect who was responsible for the nineteenth-century restoration of the cathedral. Some critics have pointed out that there are a number of clear glass windows in the church that would be better candidates for replacement. Paradoxically, the proposed windows are not particularly “contemporary”; the artist, Claire Tabouret, is no Chagall.